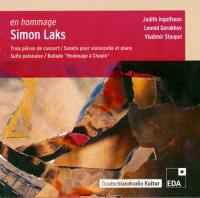

IV: Ballade "Hommage à Chopin" (1949)

Please select a title to play

I: Trois pièces de concert (1935)

I: Trois pièces de concert (1935)I: Trois pièces de concert (1935)

1 Prélude varié. Allegretto ma deciso

I: Trois pièces de concert (1935)

2 Romance. Andante con moto

I: Trois pièces de concert (1935)

3 Mouvement perpétuel. Allegro vivace

II: Sonate pour violoncelle et piano (1932)

4 Allegro moderato ma deciso

II: Sonate pour violoncelle et piano (1932)

5 Andante un poco grave

IV: Ballade "Hommage à Chopin" (1949)

IV: Ballade "Hommage à Chopin" (1949)

10 "Hommage à Chopin"

Simon Laks: A Life for Music – Survival through Music

At the end of the First World War, Poland regained its national sovereignty after 123 years of domination and oppression by the Prussian, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires. Polish artists and intellectuals were no longer driven into exile by political necessity and existential misery, as had been the order of the day since the so-called Third Partition of Poland in 1795. Besides Vienna and Berlin, Paris remained the magical center of attraction also for the generation of composers born around the turn of the century, who during the 1920s went forth to perfect their skills abroad, who precisely in the musical metropolis of Paris received the chances that were at first denied them at home. Among them was also Szymon (later Simon) Laks (1901–1983).

After studying mathematics and music in Vilnius and Warsaw, the highly talented musician enrolled in Paris' elite college, graduating in 1929 with several prizes. Although his style lacks any kind of conservatory-conservatism, the traces of the workmanlike versatility attained there – which would later save his life – are nevertheless perceivable in all his compositions: via his composition teacher Paul Vidal, a pupil of Massenet (and teacher of Nadia Boulanger), he stood in the contrapuntal tradition of the "pope of the fugue" André Gedalge; he owed his profound knowledge of the instruments and the alchemy of their orchestral mixtures, elegance, and formal perfection to his conducting teacher Henri Rabaud, the today – certainly unjustly – forgotten, longtime director of the Conservatoire. Laks, who was also very gifted linguistically, quickly forged his way. He became involved in the "Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais" (Association of Young Polish Musicians), founded in 1926 by Piotr Perkowski, which was closely affiliated with the "Ecole de Paris" and supported by Alexandre Tansman, the then most successful Polish composer living in Paris. Laks performed administrative duties within the Association, which enriched Parisian musical life before the Second World War with interesting colors and impulses, and profited himself from the numerous events and concert organized by the society.

To be sure, commissions from the major opera houses and orchestras failed to materialize – at least his Blues symphonique was honored with the Association's prize – but in the field of art song and chamber music he achieved a breakthrough by the mid 1930s at the latest. His friendship with the legendary Polish singer Tola Korian resulted in a series of exquisite settings of important Polish poetry (Tuwim, Sliwiak, etc.); the internationally renowned Roth Quartet added his Second String Quartet to its repertoire; the Cello Sonata was composed for Maurice Maréchal, the most famous French cellist of the time, who premiered it with the no-less-famous Ravel specialist Vlado Perlemuter; for the former solo cellist of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Gérard Hekking, who was Professor at the Conservatoire from 1927, he wrote the Trois Pièces de concert, which he also published in a later lost version for violin that has been reconstructed for the present recording.

With the outbreak of the Scond World War, Laks's Parisian career came to an abrupt end. As a Polish citizen of Jewish descent, he did not manage after France's surrender to escape to the unoccupied "free zone" or to emigrate, as his friend Alexandre Tansman was able to do at the last minute. Betrayed by collaborators, he was deported on 14 May 1941 to the Pithiviers transit camp near Orléans, and from there on 16 July 1942 to the Auschwitz II-Birkenau extermination camp. Through an "endless series of miracles", as he put it himself, Laks escaped the Shoah. Decisive was his transfer from a labor brigade to the men's orchestra, to which he first belonged as a musician, then as arranger, and ultimately as its director. In 1944 followed an odyssey via Sachenhausen to the Falkensee (near Berlin) and Kaufering labor camps, the latter a subcamp of the Dachau concentration camp from which he was liberated at the end of April 1945. Laks recorded his experiences in Auschwitz in his book Music of Another World (Polish: Gry Oświęcimskie; German: Musik in Auschwitz; French: Mélodies d'Auschwitz), which numbers among the most important documents about the function of music in the German concentration and extermination camps.

After his "survival through music", Laks returned to Paris to a "life for music". However, performances of his works in France and Poland, including the Warsaw television production of his captivating opéra comique L'Hirondelle inattendue [The Unexpected Swallow], and honors – such as the prize of the Warsaw Chopin Competition for the piano ballade Hommage à Chopin (written to mark the hundredth anniversary of Chopin's death), the 1965 Grand Prix de la Reine Elisabeth in Brussels for his Fourth String Quartet, or the Grand Prix of the 1964 Divonne les Bains Competition for his Concerto da Camera – disguise the fact that it was only with difficulty that he was able to hold his own in postwar musical life. The network of the "Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais" no longer existed. While in the 1930s he was a respected member of a musical movement that saw itself obliged to the modern spirit, during his second Parisian exile he became increasingly isolated. Whereas before the war his compositions were ultramodern, so to speak, he could not follow the radical stylistic change of the 1950s, or subscribe to the precepts and verdicts of the postwar avant-garde. The focus of his activity shifted increasingly to writing, translating, and – for his brother's company – to the subtitling of movies.

Laks returned from the war physically and psychologically scarred. The experience, as a Pole as well as a Jew, of having escaped the fate of the collective extermination, lastingly informed his creative work: impressively in the Third String Quartet sur des motifs populaires polonais, composed immediately after his liberation, in which Laks sketches, so to speak, the imaginary musical map of his devastated homeland; in the Poème for violin and orchestra from 1954, which was written without the prospect of a performance after a longer hospital stay necessitated by the aftereffects of the deprivations experienced in the concentration camps, and which remained unperformed during the composer's lifetime; in the songs on texts by his fellow-sufferer in Auschwitz, Ludwig Zuk-Skarszewski; in the Huit Chants populaire juifs of 1949; and in the gripping Elégie pour les villages juifs, from 1961, on a text by Antoni Slonimski. The two last-named works experienced a sustained reception during the composer's lifetime, particularly in Poland.

With the exception of the Ballade – a bravura work that is more than just a stylistic copy – the pieces on the present CD all date from before the war. They show a composer at the pinnacle of youthful mastery, who moves in the area of tension between tradition and contemporaneity, between restoration and innovation. The term "neoclassicism" can be used here to describe the overall stylistic concept, if one defines it broadly enough. Characteristic is above all the amalgam of different national influences and impressions – which is fundamentally true for the "Ecole de Paris" as well as for the group of "young Poles": Laks's music is simultaneously Polish and French, displays Slavic and Romanic characteristics, and is above all free of everything that one generally tends to define as German qualities: fecundity, complexity, profundity... Instead of that, incisiveness, wit, irony, and a propensity for playful virtuosity everywhere, but also great soulfulness in the slow movements. Traditional Polish songs and Polish dances are just as present as are jazz rhythms and harmonies. Standing discreetly in the background as godparents are Szymanowski on the one side, Ravel on the other: the Suite polonaise, composed and also orchestrated in 1936, and dedicated to Szymanowski, is based on original Polish songs, like the subsequent Third String Quartet. The sources from which Laks drew in these two cases are not known (he may have found the poignant, unusual first theme of the slow movement, with its minor triad arpeggio leading to a major seventh, in the Forty Polish Folk Songs published in 1926 by Jósef Koffler). The proximity to Ravel is shown in the first movement and in the "Blues" of the Cello Sonata, as well as in the "Mouvement perpétuel" of the Trois pièces de concert, movement forms that are also found in Ravel's Violin Sonata (1922–27). On the other hand, in the third movement of the Cello Sonata with its irregular five-measure groups and jazz harmonies, one hears the rhythmic caprices of a Dave Brubeck 'avant la lettre'.

Besides Simon Laks, other Polish composers of Jewish descent survived the Shoah. Wladyslaw Szpilman and Andrzej Czajkowski eluded death in the Warsaw ghetto, Alexandre Tansman, Grzegorz and Jerzy Fitelberg, Ignace Strasfogel, Karol Rathaus, and Paul Kletzki were able to flee in time to the USA, Mieczyslaw Vainberg to Russia, Czeslaw Marek to Switzerland. Some, such as Joachim Mendelson and Jósef Koffler, did not escape extermination, and of many others only the names remain. Simon Laks fell silent as a composer in 1967 in view of the renewed existential threat to the Jewish people that led to the Six-Day War.

Frank Harders-Wuthenow

Translation: Howard Weiner