III: Simon Laks – Divertimento (1966)

Please select a title to play

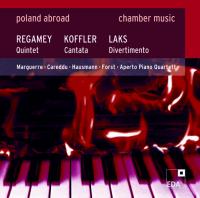

I: Constantin Regamey – Quintet (1944)

I: Constantin Regamey – Quintet (1944)I: Constantin Regamey – Quintet (1944)

1 Tema con variazioni

I: Constantin Regamey – Quintet (1944)

2 Intermezzo romantico

II: Józef Koffler – Love (Miłość), Cantata op. 14 (1931)

4 Adagio – Vivace – Un poco mosso – Tempo I

III: Simon Laks – Divertimento (1966)

8 Allegro non troppo quasi una marcia

III: Simon Laks – Divertimento (1966)

10 Molto allegro e giocoso

In the period following 1 September 1939, after just twenty years of national independence, the young Polish nation was crushed by a wave of violence that in terms of horror exceeded everything that the country had suffered previously in the 123 years of occupation, between 1795 and 1918, by the Prussian, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian monarchies. The systematic extermination of European Jewry by Nazi Germany was carried out on Polish soil. Assisted by Stalin’s Red Army during the first months of the war, the SS and Wehrmacht also killed nearly a quarter of the non-Jewish population of Poland through acts of war, punitive measures, and indiscriminate executions. Six million people lost their lives in this country.

Destroyed and forbidden was everything that could strengthen or sustain the national self-confidence – and with that the resistance. Secondary schools and universities, theaters, broadcasting corporations, opera houses, and concert halls were closed in as far as they had not already been reduced to rubble by the bombardments in September 1939, or had been “Germanized” by means of German re-establishments as, for example, in Krakow, the administrative center where Governor-General Hans Frank held court like a king. Hardly an action in this context was of such highly symbolic importance as the removal of Warsaw’s Chopin monument in 1940. However, the legendary Polish resistance was stirred up rather than broken by such actions. Music became a weapon against the degradation, became a medium of self-esteem, cultural self-reassurance, and consolation.

Professional music life moved into the private domain, into the underground, and into the coffee houses that became the (always dangerous, since threatened by police raids) meeting places of the intellectual resistance. Music-making was allowed in the ghettos under very strict constraints, and even ordered in the extermination camps. Music was made under dramatic, desperate, and often cynical circumstances. Of thousands of Jewish musicians, only a few survived the war and the Shoah. The majority were sent to the gas chambers, shot, or died of disease and emaciation.

The present recording came into being in connection with the exhibition “Music in Occupied Poland 1939–1945,” curated by the Polish musicologist Katarzyna Naliwajek-Mazurek, in which the ramifications of the destruction of Polish musical life during the occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany were systematically evaluated for the first time. In Chopin year, 2010, it was to be seen in a French version at the festival “musique interdites” in Marseille, in a German version at the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival in Hamburg and Kiel, and in a Polish version at the Warsaw Autumn Festival. At the opening of the exhibition in Hamburg, the Aperto Piano Quartet and friends performed works by Szymon Laks, Constantin Regamey, Roman Padlewski, and Jósef Koffler. The musicians played the program again in somewhat altered form at the presentation of the project in Berlin in October/November 2010 in collaboration with Berlin’s Academy of the Arts and the Academy of Music Hanns Eisler. In January and April 2011 followed the recording sessions for the three works documented by this co-production with Deutschlandradio Kultur. Although only Regamey’s Quintet was composed during the time period documented by the exhibition, the fate of all the composers is representative of that of music in Poland during the Second World War.

“The virtual certainty that he would not survive the war

and the complete isolation in occupied Warsaw also meant

that he found himself in a situation of complete freedom.”

Jürg Stenzl

Among the courageous musicians who were active in the Polish resistance was Constantin (Polish: Konstanty) Regamey (1907–1982), one of the most fascinating personalities not only of the musical history of the twentieth century. His complex family tree consists of Swiss branches via his great-grandfather Louis Regamey from Lausanne, who immigrated to Vilnius and later settled in Kiev; through his great-grandmother came Polish, through his grandmother Hungarian and Italian, and through his mother, who had grown up in Russia, Swedish and Serbian branches. When Constantin was born in Kiev in 1907, his family was already Polish to the core. In 1920 his mother settled with her second husband, a Polish officer, in Warsaw, where Constantin finished school and university studies, and began a brilliant career as lecturer in Indology at the university. On the side, he dedicated himself, no less professional, to music criticism: he published his first review at the age of sixteen, and in 1937 became editor of the leading Polish music periodical Muzyka Polska. After the Nazis closed down the Warsaw University, he became active in several committees of the Secret Music Council, a division of the Polish underground that worked to maintain the cultural life and to care for destitute musicians during the Nazi occupation. After initial attempts at composition as a youth, 1942 saw the creation of his op.1, the Chansons persanes, which was premiered at a remarkable underground concert and in which he already experimented with Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique. However, the premiere of his Piano Quartet on 6 June 1944, only a few weeks before the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising, will be remembered as a central event in Polish musical history. Among the musicians in attendance was also Regamey’s close friend Witold Lutosławski, who after the war wrote down his memories of the event: “One recognized that one was confronted by an entirely mature, highly sophisticated work completely independent of everything that at that time constituted the style and form of the Polish musical culture of the 1930s and 1940s. Not surprisingly, since it was the first dodecaphonic work to be written in Poland. (The first representative of twelve-tone technique in Poland was indeed Józef Koffler, who at this time lived in Lviv; in Warsaw, however, one knew nothing of his activities) But the technique alone would not have been sufficient to make the premiere seem so sensational. Many factors contributed to it, but particularly the composer’s extraordinary creative power and his entirely personal manner of employing Schoenberg’s methods have to be noted.”

Regamey’s Quintet is an exceptional work in every respect. Written under conditions in which one had to reckon each day with being shot dead or becoming dangerously ill, as the op. 2 of a composer who had never attended a class in composition, it is astonishing in its dimensions, its unusual instrumentation, and its extraordinary virtuosity. It was composed by someone who did not have to show consideration for any prevailing tastes or expectations. As Swiss musicologist Jürg Stenzl rightly notes, it is – like Olivier Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps, which has a similar instrumentation and was likewise written under dramatic circumstances – music that is probably to be understood only out of this experience of the “end of time.” Regamey’s extraordinary gift for languages – as a linguist, he was fluent in over twenty languages – finds its correlate in the astounding diversity of the “idioms” and compositional techniques that “have their say” in his Quintet, a piece that however has nothing eclectic or arbitrary about it. Here, an encyclopedic spirit tallies the balance of his epoch, an epoch that is disjointed, and in doing so does not rest on terrain secured by others. Grotesque masks à la Shostakovich and Prokofiev are means of expression for a life situation experienced as “surreal,” and Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique tellingly serves in the “Intermezzo romantico” as a safety net for a last glance back at the nineteenth century.

Following the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising, Regamey was arrested and incarcerated in the Stutthof concentration camp (near Danzig). Thanks to his Swiss citizenship, he was deported to Switzerland, where he was not only able to continue his career as one of the world’s leading Indologists and linguists at the Universities of Fribourg and Lausanne, but also as one of the most renowned Swiss composers. Polish musicology has accorded him a place in their music history, as has Swiss musicology in theirs. However, throughout his life, he felt himself particularly obliged to Polish musical life, and also had his works published in Poland after the war, was performed more regularly in Poland than in Switzerland or Germany, and maintained very close contact with his Polish musician friends until his death.

“ ... but have not love ... “

Paul, 1 Corinthians

As Lutoslawski correctly stated in his recollections of the premiere of Regamey‘s Quintet, the first dodecaphonic work of Polish music history did not stem from Regamey’s pen, but rather from that of the Lviv componer Josef (Polish: Józef) Koffler (1896–1943). Nevertheless, Koffler, who is today considered the most important pioneer of Contemporary Music in Poland, was less well known in the Warsaw circles of the pre-war period than abroad, where his works were regularly to be found on the programs of the festivals sponsored by the International Society for Contemporary Music. Born in Stryi, Galicia, Koffler went to Vienna in 1914 to study law and music (composition, conducting, and musicology). After military service in the Austrian army, he earned a doctorate in 1923 under Guido Adler with a dissertation on “orchestral color in the symphonic works of Mendelssohn,” and settled in 1924 in Lvov, where he held the then only professorship in Poland for atonal compositional techniques. Koffler, who had become friends with Alban Berg in Vienna, never personally met Arnold Schoenberg, with whom he corresponded starting in 1929 and as whose pupil he is sometimes referred to. The occupation with Schoenberg’s method was however decisive for his works, and indeed starting already in 1926, thus making him one of the pioneers of dodecaphony. A comparison of his Cantata on the words of St. Paul, composed in 1931, with Regamey’s Quintet shows the profoundly different results that the use of Schoenberg’s theory can lead to, and how greatly these results were determined by the artistic intentions of the respective composer. Even though Regamey’s assurance, that the twelve-tone technique in no way served him “to replace tonality, but solely to supply a polyphonic discipline and to create an internal, thematic, and harmonic unity,” is no less true of Koffler’s work, the stylistic positions of these two pieces are worlds apart. If the row (or the rows) served Regamey as the raw material for the organization of complex harmonic and melodic processes in which the thematic “personality structure” of the row functions rather like a genetic code, in Koffler it comes to the fore dominantly, that is to say, melodically-thematically. Koffler’s row is moreover modeled on heavily affect-laden models of the musical past (minor sixth upswing like at the beginning of Wagner’s Tristan, descending line with chromatic progressions in accordance with the Baroque “passus duriusculus”) and made with a second half that leads to a cadence on the “keynote,” through which a feeling of “tonal” cohesion ensues. If Regamey’s Quintet is distinguished by epic dimensions and an excessive abundance of ideas, Koffler finds his way to a maximum concentration and intimacy of expression that is very near to the gesture of several of Bach’s late works.

After the annexation of western Ukraine by the USSR in September 1939, Koffler assumed the professorship for composition at the State Mykola Lysenko Conservatory and the post of prorector. That same year he was appointed as secretary of the Composers’ Association of Soviet Ukraine. There followed a short period of secure existence and professional stability, even though he was compelled to bow to the dictates of socialist realism following an accusation of formalism. After the capture of Lvov by the Germans in 1941, he and his family were resettled in the Wieliczka ghetto. The circumstances of his death are still not completely clear. After the liquidation of the ghetto in 1942, the family was apparently able to hide near Krosno, where they were discovered by a German Einsatzgruppe (deployment group) and killed in a mass execution.

“Hélas! Hélas! La morte violente est de nos jours fréquente.”

Simon Laks/André Lemarchand L’Hirondelle inattendue

Szymon Laks (1901–1982), who Frenchified his first name to Simon, was one of the group of young Polish musicians who came together to form an artists’ federation in Paris in 1926 and, as former students of the Conservatoire and Nadia Boulanger’s private academy, soon made names for themselves in Parisian musical life. Supported by Alexandre Tansman and associated with the aesthetic ideals of néoclassicisme, the then musical elite of Poland – who had either settled permanently in France or, as returnees, provided important impulses for the development of Polish musical life of the late 1920s and 1930s – joined together in this “Association des Jeunes musiciens polonais.” Laks, who was born in Warsaw and, after studies in Vilnius and Warsaw, went to Paris by way of Vienna, played an important role in the Association. He had graduated from the Conservatoire with honors and composed since the beginning of the 1930s for a number of prominent musicians and ensembles, including for the Quatour Roth, and the legendary Ravel specialists Vlado Perlemuter and Maurice Maréchal, the most renowned French cellists of the time.

Imprisoned in 1941 because of his Jewish descent, Laks was deported in the summer of 1942 to the Auschwitz II-Birkenau extermination camp, where due to his wide-ranging musical skills he was assigned to one of the camp orchestras as violinist, arranger, and, ultimately, director. Laks survived the extermination camp and, from 1944, several labor camps “thanks to an endless series of wonders,” as he later summed it up in his book Music of Another World.

The Divertimento, premiered in 1966 in Salle Pleyel by the Ensemble Instrumental Paris, was written a year after the composition of Laks’s main work, the opera L’Hirondelle inattendue (“The Unexpected Swallow,” eda 35), shortly before he quit composing under the impression of the Six Day War and the new state-sanctioned anti-Semitism in Poland and turned to literary pursuits. Alongside the Cello Sonata, the String Quartets 3–5 (the first two, which were written before the war, are lost), and the 3 Pièces de concert, the Divertimento numbers among Laks’s most successful chamber music works and shows his neoclassicism-obliged aesthetics at its very best. As also with the other Polish composers who worked in Paris and were informed by two very different cultures, impressive in Laks is the successful combination of French clarité – precision, conciseness, humor – and an inwardness and melodic intensity of feeling fed by native Polish sources.

Listening to it superficially, the compositional mastery and the formal perfection displayed in the Divertimento belie the stumbling blocks with which Laks confronts his musicians and audience. A keen instinct is necessary in order to grasp the character of this music, its gradations between lyrical tenderness and mercurial whim. Laks proves himself to be a master of ambivalence already in the introduction of the first movement, a march that starts to hobble due to its irregular meters, but which has nothing caricature-like about it. Several masses of sound are set into motion from which the finely chased, rhythmically pointed writing of the transition is able to set itself off. Virtuoso interaction, a certain amount of acrobatics and, in any case, precision work is demanded. And indeed increasingly so in the breakneck third movement in which the musicians toss the balls back and forth in breathtaking tempo. One might tend to think that it is l’art pour l’art, music for its own sake. In any case, the complete opposite of a music that attempts to come to terms with the Shoah by means of tones. Laks – who with his first book did not write a book about Auschwitz, but rather one about the music in Auschwitz, a fact he considered important to emphasize – would have found it abhorrent to burden tones with the unspeakable horror that he was forced to see and endure for years. Anyone who witnessed the perversion of music in the Germans’ killing machinery would not even indirectly want to let the Nazis enter his art again. Laks found other ways to commemorate the destruction of the Polish and Polish-Jewish cultures. For example, by letting the indestructible relics of these cultures speak for themselves, as in his Third String Quartet “on Polish themes” (1945), or in his arrangements of Yiddish folksongs, the Huit chants populaires juifs (1947). In the A section of the second movement, he discreetly quotes a passage from his opera L’Hirondelle inattendue (“The Unexpected Swallow”), a strikingly introverted moment in the context of the opera on the words “Hélas! Hélas! La morte violente est de nos jours fréquente” (Woe! Woe! Violent death is frequent nowadays). Only those who know the opera will notice the allusion, and it is only to be understood against the background of Laks’s biography. In a world that can instantly return to business as usual even after mankind’s greatest catastrophe, one has to shout in order to be heard. Laks, the master of understatement, preferred the quiet tones and, ultimately, silence.

Frank Harders-Wuthenow