XII: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.4 Op.38 (1941)

Please select a title to play

I: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.7 (1943)

I: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.7 (1943)I: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.7 (1943)

01 Allegro

I: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.7 (1943)

02 Alla marcia

I: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.7 (1943)

03 Adagio, ma non troppo

I: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.7 (1943)

04 Allegretto grazioso

I: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.7 (1943)

05 Variations and Fugue on a Hebrew Folk Tune

II: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.1 Op.10 (1936)

07 Andante (quasi marcia funebre)

II: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.1 Op.10 (1936)

06 Molto agitato

II: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.1 Op.10 (1936)

08 Adagio - Presto

III: Norbert von Hannenheim - Sonata No.2

09 Andante

III: Norbert von Hannenheim - Sonata No.2

10 Allegro molto vivace

IV: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.2 Op.19 (1938/39)

11 Allegro energico e agitato

IV: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.2 Op.19 (1938/39)

12 Theme and Variations on a Moravian folk tune

IV: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.2 Op.19 (1938/39)

13 Prestissimo

V: Norbert von Hannenheim: Sonata No.4a

14 Allegretto

V: Norbert von Hannenheim: Sonata No.4a

15 Allegro molto vivace

VI: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.6 (1943)

16 Allegro molto

VI: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.6 (1943)

17 Allegretto grazioso

VI: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.6 (1943)

18 Presto, ma non troppo

VI: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.6 (1943)

19 Allegro molto

VII: Norbert von Hannenheim: Sonata No.12

20 Adagio

VII: Norbert von Hannenheim: Sonata No.12

21 Allegro

VIII: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.3 Op.26 (1940)

22 Allegro grazioso, ma agitato

VIII: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.3 Op.26 (1940)

23 Scherzo - Allegro violente

VIII: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.3 Op.26 (1940)

24 Variations on a Theme by Mozart

IX: Norbert von Hannenheim - Sonata No.6

25 Allegro vivace

IX: Norbert von Hannenheim - Sonata No.6

26 Andante

IX: Norbert von Hannenheim - Sonata No.6

27 Vivace

X: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.5 (1943)

28 Allegro con brio

X: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.5 (1943)

29 Andante

X: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.5 (1943)

30 Toccatina

X: Viktor Ullmann - Sonata No.5 (1943)

31 Serenade

XI: Norbert von Hannenheim - Sonata No.3

33 Molto Allegro

XI: Norbert von Hannenheim - Sonata No.3

34 Adagio

XII: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.4 Op.38 (1941)

36 Allegro vivace

XII: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.4 Op.38 (1941)

37 Adagio

XII: Viktor Ullmann – Sonata No.4 Op.38 (1941)

38 Finale

Albert Breier

On the rightfulness of musical form

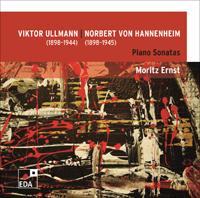

Viktor Ullmann and Norbert von Hannenheim: Piano Sonatas

In the 20th century, it often suffices to know a person’s biographical dates and certain life stages in order to get an idea of his or her experiences and their fate. Being born in 1898 means: witnessing World War I during the formative years of late adolescence; attempting to establish oneself during the Twenties – a time that was hardly “golden”, but rather downright chaotic – and eventually, after 1933, living through increasing darkness and danger of death. Viktor Ullmann and Norbert von Hannenheim were both born in 1898, one in the Silesian town of Teschen, the other in the Transylvanian town of Hermannstadt. Both were soldiers in World War I. After the end of the war, both had to struggle to have their compositional works acknowledged; after 1933, public artistic development became impossible. Ullmann was murdered in Auschwitz in October 1944 and Hannenheim died in a psychiatric institution in September 1945. These dates of death evoke strong images connected with this epoch; these were years of terror, unparalleled in human history.

Ullmann and Hannenheim spent their lives almost exclusively in the territory of Germany and the Austrian monarchy, which ceased to exist in 1918. As musicians, they became heirs to a great and formative tradition. Both studied with the composer who was regarded as the most excellent advocate of this tradition, Arnold Schoenberg. With great effort, Schoenberg had developed his twelve-tone method during the years following the collapse of Austria-Hungary in order to ensure the autonomy of music and its continued existence during an age of subversion. The immense pressure that bore down on his undertakings is reflected in the works from that period, many of which even exhibit exemplary character, e.g. his Wind Quintet op.26, the Third String Quartet op.30, or the Orchestra Variations op.31. In their works composed during and after the late 1920s, Ullmann and Hannenheim both built on such compositions. However, the forms used by both are frequently shortened – in contrast to Schoenberg’s Wind Quintet, where they are considerably extended – thereby emphasizing their exemplary character. None of the three movements of Hannenheim’s Piano Sonata no.6 lasts longer than three minutes; the third movement of Ullmann’s Sonata no.5 only lasts three quarters of a minute. Ullmann and Hannenheim avoid the four-movement norm of the 19th century. They both refrain from inserting lightweight scherzo or minuet movements. Ullmann favoured a three-movement structure in his earlier sonatas. Hannenheim even formed two-movement constructs following the example set by Beethoven’s op.78, 90, and 111. In Ullmann’s later works, however, expanded pieces resurface. This is related to the development of a greater stylistic variety, which is expressed by an extended tonality that is characteristic for Ullmann. Hannenheim, on the other hand, seems to have increasingly withdrawn himself during the 1930s. While Ullmann banks on fullness and diversity, Hannenheim focuses on scarcity and internal tension.

Thanks to Schoenberg and his school, the contrapuntal thinking experienced a pronounced revaluation, which also had an influence on instrumental notation. The hefty romantic sound of the piano, often replete with tone doublings, gives way – in Hannenheim’s works even more so than in Ullmann’s – to a wiry latticework, which no longer exhibits superfluous thickening. Ullmann and Hannenheim oppose the mere textbook counterpoint of neoclassical composers with the precision and rigidity of strictly shaped lines; this results in extremes such as the strangely bare two-part note-against-note counterpoint at the beginning of the Adagio in Hannenheim’s Sonata no.3, a structure that gains great expressiveness from the amalgamation of unobtrusiveness and implacability. Hannenheim conceives the second movement of his Sonata no.6 as Passacaglia. Ullmann’s works also exhibit contrapuntal forms although he has a preference for the fugue. Ullmann’s and Hannenheim’s tendency towards contrapuntal discipline can be understood as a necessary counterpart to a freely flowing imagination, which often juxtaposes opposites. Ullmann can create variations from simple and seemingly familiar themes, which appear to be completely dissolved and facilitate the bizarre and the grotesque. In this case, as well as in many of Hannenheim’s pieces, one could speak of a structural eeriness. The familiar becomes strange, friendly characters transform into sinister figures, and yet, they are all built from the same stock of notes. This is music from a time in which boundaries dissolve, all identities become indeterminate, and solid points of reference seem no longer to exist; a time in which the alert “I” is subjected to severe psychological strain.

Both Hannenheim and Ullmann lived through periods of severe psychological crisis. In this context, the problem of the doppelgänger is very important for both of them. Ullmann dealt with the problem in his “diary in verse” Der fremde Passagier (The estranged passenger). In Hannenheim’s case, the problem of the doppelgänger had a direct influence on the musical composition. In his music, the acknowledgement of unquestionable identity, which forms the beginning of the western musical rulebook, remains unfulfilled in almost every aspect of musical formation. If his musical ideas seem to have a counterpart at first, a detailed analysis will reveal that the commonalities are greater than the differences. The themes of Hannenheim’s “B sections” are either restatements of the exposed figures from the “A sections” or they are – in a characteristic way – their shadows. In his serial compositions, Hannenheim can even introduce new rows, without anybody getting the impression of being confronted with new material. It does not make a difference whether or not these new rows may be linked to the initial row in simple or more complicated ways. Hannenheim’s multiple “I” does not acknowledge traditional rules, and yet, he is not free. The “I” and its doppelgängers act under the same constraint; a constraint that is not determined by human authority and whose mode of operation can neither be understood nor suspended by any human being. The number of doppelgänger figures can be of any size in Hannenheim’s works, so that the term “primordial figure” becomes arbitrary. A particularly eerie effect arises in one’s conscious perception when two figures with a doppelgänger relation appear simultaneously. Initially one figure takes the lead, but is then quickly replaced by the other: someone who marched behind me, suddenly stands in front of me, without me having noticed when or how he overtook me. In other cases, the doppelgänger figure is not instantly recognisable as such; its true nature has to be revealed. Hannenheim seems to know that all musical figures are yet to be revealed doppelgänger figures.

Hannenheim appears to have been quite familiar with white and black magic and he apparently attributed magical powers to himself. Ullmann, too, conducted esoteric studies; from time to time he was close to anthroposophy. Moreover, both Hannenheim and Ullmann exhibit certain closeness to the mystic world of Alexander Scriabin in their music. In Hannenheim’s works – for example at the beginning of his Piano Sonata no.6 – one can sometimes detect the “flights of fancy” that are so typical of Scriabin. In later years, Ullmann developed a harmonic language that partly corresponds to the harmonic system of the Russian symbolists, which in turn has its source in the so-called mystic chord. Unlike Scriabin, however, neither Ullmann nor Hannenheim take the listener to a mystic dreamland. Stefan George’s “air from other planets”, invoked in the final movement of Schoenberg’s Second String Quartet, has only been ever so slightly hinted at by both composers. The home of their music is this world, populated by people and demons.

The tendency towards the magical – to which Arnold Schoenberg, too, frequently gave in – can be interpreted as the hope to find refuge in transcendental regions in times of uncertainty and rapid change. The attempt has to remain ambivalent. One of Hannenheim’s statements from the late 1930s says: “We live in a time of change. There’s all hell, all devils let loose. I’m a devil, too.” Like every magician, Hannenheim sometimes had doubts about the rightfulness of his doings. He sometimes wondered whether his creations were products of forbidden black-magical ambitions. It is therefore possible that his attempt to destroy his works stemmed from these doubts. Time and again, Hannenheim set the virtue of the form that is legitimated by tradition against the rampant magical being, thereby conforming to Ullmann. In Hannenheim’s works, the great abstractness of his musical thinking may be associated with the Berlin atmosphere. Ullmann, on the other hand, could draw on the overwhelmingly rich source of Bohemian music.

The gruesome aspect of life in the early 1930s was the fact that everyone, even your neighbour, could be an unrecognised foe. This neighbour could have resembled yourself in every way, and yet, he sought to destroy you. When this foe eventually emerged in the shape of the Nazis, it sometimes still maintained its friendly appearance: the people of Theresienstadt were allowed to make music; a “cultural life” was presented to the world. For Viktor Ullmann, the possibility to compose new music in Theresienstadt fuelled his will to live. In his essay Goethe und Ghetto, he states:

“Theresienstadt was and remains a school of form for me. In former times – where we were unable to experience the weight and load of the material life, because comfort, this magic of civilisation, enabled us to disregard it – it was easy to create beautiful form. Here, one has to overcome the material with form in everyday life, every bit of music stands counter to its surroundings: This is the true master class. It is here that one sees the purpose of artwork in Schiller’s words: “material must be consumed by form”. Presumably, this is the true mission of mankind – and not just of aesthetic, but of ethical mankind as well.”

The smaller Ullmann’s sphere of influence became, the broader his horizon grew. This is manifested in his last piano sonatas. Music from different cultures influenced his works as well as chants from different religions. The final movement of the Sonata no.7 is comprised of variations on a Hebrew folk song. However, the protestant chant Nun danket alle Gott (Now thank we all our God) also appears in this movement as does the Hussite chant, whose text hints at the sources from which Ullmann drew the strength for his artistic work:

You, who are God’s warriors,

And subjects of His righteousness,

Pray to God for His help and put your trust in Him,

That with Him you shall be victorious in the end.

Ullmann generally prefers the form of variation. He sees in it the possibility to develop a great stylistic and compositional variety in a compact space, while the consistent theme guarantees coherence. Ullmann’s themes originate from entirely different backgrounds: sources for his works may range from Hebrew tunes to the early Mozart (the third movement, Andante grazioso, of Sonata no.3). The theme of the Second Sonata’s second movement is based on a Moravian folk song as recorded by Leoš Janáček. Ullmann must have studied this particular piece by the Brno master most thoroughly. It is doubtful, however, that he also had the opportunity to listen to Janáček’s last opera From the House of the Dead. Its plot is set in a Russian prison camp. The prisoner’s will to live is most impressively articulated through Janáček’s music with its relentless intensity. Music that comes from the camp can indeed bear witness to freedom, just as works that were composed in a “free” environment may carry signs of restriction and coercion. Whether a constraint is self-inflicted or imposed by a third party will make all the difference. The twelve-tone method was perceived as a constraint by only those composers who regarded it as an extrinsic and impersonal set of rules. Both Ullmann and Hannenheim studied the serial technique but never created dogmatic twelve-tone pieces. In Hannenheim’s compositions, the number of tones in a row may exceed twelve. Ullmann, following Alban Berg, strived after a conciliation of serialism and tonality.

Numerous works by Ullmann and Hannenheim have been lost due to the circumstances of the time. Surviving records give an idea of the extent of loss. Where Ullmann is concerned, the majority of lost works originated in the 1920s and 30s, while almost all the Theresienstadt works have been saved. Hannenheim is known to have composed approximately 230 works, 45 of which have survived as of today. Therefore, even a vague assessment of Hannenheim’s oeuvre proves to be difficult. In the case of his piano sonatas, which are assumed to have been composed during the 1930s, one has to take into account that Hannenheim loved to combine compositions of the same kind to groups of three, six or twelve, as it was the custom from the Baroque to around 1800. The position of a sonata within this group should affect its analysis and interpretation. However, this is no longer possible. Although Hannenheim’s and partly Ullmann’s oeuvre has only survived in fragments, this fragmentary character has never been intended by either composer. Above all, it does not conform to their aesthetics. Despite all scarcity, their works seek completeness; they forge bridges that do not tolerate disruption. By fortunate coincidence, apparently all of Ullmann’s piano sonatas survived. The series of works composed between the years 1936 and 1944 can be regarded as compendium of Ullmann’s art of composition.

In a letter written in 1944, Anton Webern, another Schoenberg student, quotes Hölderlin: “Life means defending a form”. Form is that which justifies an artist’s work and existence. For Ullmann and Hannenheim it meant righteousness during times of injustice. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben declared the concentration camp — and not the state — as bio-political paradigm of the Western world. The camp inmate could be handled politically without being granted the right to existence. The artist’s response to the situation in the camp is the appeal to the artistic form, which is also a legal form for him. The crisis of the form in modern art is primarily a crisis of its legitimacy. This crisis is yet to be overcome. For the Nazis, music in Theresienstadt came under the heading of Freizeitgestaltung (“recreational activity”). However, this way of denying art any higher legitimisation has not been eliminated with their downfall. The music of Viktor Ullmann and Norbert von Hannenheim bears witness to their faith in a high purpose of artistic endeavour. It demonstrates vitality through its power of form, wrested from the most adverse of conditions. This is what makes us appreciate and honour their music especially today.

Note

The arrangement of this recording’s sonatas neither reflects their numbering nor their chronological order. It was chosen in order to ensure a varied listening experience and to bring some facets of Ullmann’s and Hannenheim’s compositional craftsmanship into prominence. The arrangement of Ullmann’s sonatas reflects an increasing degree of complexity of the fugal movements. By contrast, Hannenheim’s sonatas are arranged by increasing levels of relaxation. The presentation of Ullmann’s and Hannenheim’s works in alternating order highlights the contrasting personal idiosyncrasies of the two composers. At the beginning, Ullmann’s last sonata is juxtaposed with his first, thereby already forging the bridge on which the music of both composers develops all its diversity and richness.