III: Simon Laks – String Quartet no. 5 (1963)

Please select a title to play

I: Joachim Mendelson – String Quartet no. 1 (c. 1925)

I: Joachim Mendelson – String Quartet no. 1 (c. 1925)I: Joachim Mendelson – String Quartet no. 1 (c. 1925)

1 Moderato con spirito

I: Joachim Mendelson – String Quartet no. 1 (c. 1925)

2 Largo

I: Joachim Mendelson – String Quartet no. 1 (c. 1925)

3 Allegro con brio

II: Roman Padlewski – String Quartet no. 2 (1940–42)

4 Praeludium in modo d'una toccata

II: Roman Padlewski – String Quartet no. 2 (1940–42)

5 Introduzione e Fuga

III: Simon Laks – String Quartet no. 5 (1963)

7 Allegro moderato

III: Simon Laks – String Quartet no. 5 (1963)

8 Adagio molto

III: Simon Laks – String Quartet no. 5 (1963)

9 Scherzo. Quasi presto

III: Simon Laks – String Quartet no. 5 (1963)

10 Allegro giocoso

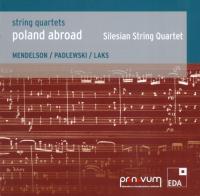

After first recordings of works for string orchestra (vol. 1, EDA 26) and of symphonic poems (vol. 2, EDA 27), this third volume of the series “Poland Abroad” presents unknown Polish contributions to the string quartet genre. The selection of compositions and composers is closely connected to a core theme of the series, which is dedicated to the impact of the Second World War and the consequences of the Shoah for Polish musical life. This also explains the inclusion of Roman Padlewski in the ranks of outstanding Polish composers EDA wishes to honor with this series.[1]

Of the three composers presented here, only Szymon (in France later: Simon) Laks survived the World War and the Shoah, and this only thanks to an “endless series of wonders,” as he later acknowledged in the account of his survival. While something could be done in recent years to promote his rediscovery, it is now time to undertake this trailblazing work for Roman Padlewski and Joachim Mendelson.

What little information we know about Joachim Mendelson is still limited to that found in Isachar Fater’s standard work Jewish Music in Poland during the Interwar Period,[2] and what his publishing house, Max Eschig in Paris, was able to compile from old documents in the publisher’s archives: Mendelson and his entire family appear to have perished in the Shoah. Born in 1897 in Warsaw, Mendelson studied composition with Henryk Opieński and Felicjan Szopski at the Warsaw Institute of Music, and continued his studies in Berlin after the First World War. At the end of the 1920s he went to Paris, where he was accepted into the “Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais.” Szymon Laks, who played a leading role in the Association, aided him and endeavored to interest Nadia Boulanger in performances of his works. A letter from Laks to Nadia Boulanger, dating from 1928 or 1929, concerns an octet by Mendelson, which Laks recommends for performance by the Société Musicale Indépendante in which Nadia Boulanger is on the board of trustees.

Mendelson dedicated his String Quartet, presumably written already in Berlin, to the Roth Quartet, which performed it on tour throughout Europe. He met Karol Szymanowski and deepened his friendship with Alexandre Tansman, who introduced him to Max Eschig, who became his publisher. In 1935 Eugeniusz Morawski[3] appointed him teacher of music theory and harmony at the Warsaw Conservatory. In 1943 he was murdered in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Whoever hears Mendelson’s String Quartet for the first time, unbiased and unaware of the composer’s nationality, will probably be deceived. The style is not manifestly Polish. Rather, one would perhaps identify the composer as belonging to the Czech cultural sphere. The influence of Ravel and Debussy is found in certain timbral and harmonic aspects. The dance-like rhythms and the often modally colored melodies, on the other hand, clearly seem to be Slavic. The more one listens to the three-movement work, the more the characteristics of a personal style stand out, which is distinguished by elegance, refinement, and the naturalness of a masterful craftsmanship, a craftsmanship that, owing to the prevailing charm, the tranquil breath, and dance-like lightness of this music, never tries to propel itself into the limelight. (Characteristics that more than once call to mind the famous namesake Felix.) The proximity to French neoclassicism is evident in the clarity of the formal structure and the emotional balance.

A work of an entirely contrary nature is Roman Padlewski’s Second String Quartet, which was written in Warsaw during the war years 1940–42. Born in Moscow in 1915, Padlewski was one of the great Polish universal musical talents of his generation. Trained as a violinist, pianist, conductor, and musicologist, his first successes as a composer coincided with the outbreak of the Second World War. From November 1939 he was involved in the Warsaw underground in various functions: military, organizational, and also musical as composer, soloist, and chamber musician. During the Warsaw Uprising he distinguished himself through exceptional bravery. On 14 August 1944, while attempting to disarm a remote-controlled Goliath tracked mine, he was shot in the back by a German soldier. Since the resistance had only very few and inadequate anti-tank weapons, volunteers undertook the perilous task of manually cutting the remote-control cables of the Goliaths before they reached their targets. He died of his wounds two days later, on 16 August.

The tragic fate of the young artist was also suffered by most of his oeuvre, which was lost during the war. Of the works composed after 1939 only the Sonata for violin solo (1941), a Suite for violin and piano (1942), the Kurpian Suite (Suita kurpiowska), an arrangement for violin and piano four-hands of a selection of Karol Szymanowski’s Kurpian Songs (1941), and the Second String Quartet have come down to us. The latter was saved through an operation of the Secret Music Council. The council chose several works written during the war years that were considered particularly valuable, microfilmed them, and had the films smuggled to London by air. It was feared that they would not survive under the tragic conditions of the war.

In its range of expression, evolving between delicate soulfulness and rugged expressiveness, Padlewski’s Second String Quartet displays a certain spiritual relationship to the Alban Berg of the Lyrical Suite. It is obviously a coming to terms, reminiscent of late Beethoven, with the role model Bach that appears to be like a forward projection of this epochal dialogue over an additional century. Padlewski, however, sets his own personal, yearning, and almost addictive tone, and creates an original, processual composition technique in which the development of the material seems to follow formal-logical principles less than it does the psychogram of an underlying emotional drama. With the inclusion of cyclical elements, Padlewski expands the two-movement Baroque model of toccata and fugue to epic broadness and derives from it the tension of free improvisational and strict contrapuntal compositional techniques that increasingly permeate one another during the course of the work. Already when listening to it for the first time, one perceives that something mysteriously touching is written into the work. An at first rather inconspicuous detail, a sigh figure, that Padlewski introduces in the “Praeludium” in the run-up to the recapitulation (a portato drawn out over an octave, with subsequent descending semitone steps), receives thematic weight in the second movement until it ultimately absorbs all fugal and canonic arts and all virtuoso passage work in its unsettling lamento gesture.

Szymon Laks, born in 1901 in Warsaw, went by way of Vienna to Paris, where in 1926 he joined and became active in the organization of the “Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais,” which had been founded shortly before by Piotr Perkowski. Already by the end of the 1920s he had a certain “standing” in the Parisian musical scene. He was encouraged by Alexandre Tansman, a protagonist of the “Ecole de Paris,” and his works enjoyed performances by the renowned Roth Quartet, which had his Second String Quartet in its repertoire. The Ravel specialist Vlado Perlemuter, likewise a Polish-Jewish expatriate, performed his piano works and was also the pianist for the premiere of Laks’s Cello Sonata (EDA 31), which Laks composed especially for Maurice Maréchal, the most renowned French cellist of the time.

Laks’s career abruptly ended in 1940 after France’s capitulation when he was interned because of this Jewish descent by the authorities of the Vichy regime, which collaborated with Nazi Germany, and deported in the summer of 1941 to the Auschwitz II-Birkenau extermination camp.[4] After liberation in 1945, Laks, whose first two string quartets were lost during the war, again turned to this genre three times after long intervals. His Fifth Quartet, written in 1963, was one of his last works before he fell completely silent as a composer under the impression of the Six Day War in 1967, and henceforth devoted himself to literary works. Like other compositions of the postwar era, it experienced its premiere only years after the composer’s death, on 2 February 1998 by the Pellegrini Quartet on the occasion of a concert organized by the Fritz Bauer Institute, which had sponsored the German first edition of Laks’s book Musik in Auschwitz (published in English as Music of Another World). It is meanwhile in the repertoire of the Silesian String Quartet, which has performed it in concerts in the USA, Poland, and Germany.

In contrast to the Third Quartet and other works of the postwar era in which Laks occupied himself with the musical heritage of his native country, in contrast to works such as the Sinfonietta for Strings or the Petite Suite légère for orchestra in which ironic aphorisms in the spirit of neoclassicism dominate, other compositional tendencies typical of Laks play a role in the Fifth Quartet. Most notably, these are an austere lyricalness and a constructivist stringency in the melodic and rhythmic structure. Although quasi-tonal centers are formed and an extended pitch-level consciousness corresponding to the neoclassical formal construction as a structural foil is to be perceived, the harmony subordinates itself to the decidedly contrapuntal lines of the voices. Tonal thematic formations are abandoned in favor of symmetrical intervallic constellations and an at times excessive chromaticism. Unusual playing techniques and timbral effects are employed sparely but very effectively, for example, the ghostlike sul ponticello passages in the third and fourth movements, the latter also being the only one to play with folk-song-like elements.

Unlike the composers of the “Groupe des Six,” who were likewise obliged to neoclassicism, but already had a place in international musical life before the war and did not participate in the Boulezian and Stockhausian stylistic turn in the 1950s, the biographical break between 1940 and 1945 weighed very heavily on Laks. Too young and hardly established at the outbreak of the war, he returned neither to his native country nor to normality after the hell of Auschwitz, but to an exile in which the parameters of cultural life (and survival) had changed completely. The network of the “Jeunes Musiciens Polonais” was no longer active, and the necessary “connections” were lacking. From today’s historical distance in which criteria other than the degree of the “progressiveness of the material” are employed in the evaluation of works, an unbiased assessment and appreciation of this “lost generation” before the backdrop of the two World Wars and the aesthetic revolutions and restorations of the twentieth century has finally become possible. And one can only hope that musical life will not pass by these at long last salvaged treasures.

Frank Harders-Wuthenow / Katarzyna Naliwajek-Mazurek

[1] See the texts to vols. 1 and 2.

[2] Isachar Fater, Muzyka żdowska w Polsce w okresie międzywojennym, translated from the Hebrew by Ewa Świderska (Warsaw: Oficyna wydawnicza Rytm, 1997).

[3] See EDA Poland Abroad vol. 2.

[4] For Laks’s biography, see the booklets to “Poland Abroad” vol. 1 (EDA 26) and vol. 2 (EDA 27) and to the CD “en hommage” Simon Laks (EDA 31), which can be consulted on the EDA website, as well as www.boosey.com/Laks.