VII: Günter Raphael – Sonata op. 74a (1957)

Please select a title to play

I: Walter Girnatis – Sonatina (1962)

I: Walter Girnatis – Sonatina (1962)I: Walter Girnatis – Sonatina (1962)

1 Allegro

I: Walter Girnatis – Sonatina (1962)

2 Arietta

I: Walter Girnatis – Sonatina (1962)

3 Rondino

II: Friedrich Leinert – Sonata (1952)

4 Allegro moderato

II: Friedrich Leinert – Sonata (1952)

5 Larghetto

II: Friedrich Leinert – Sonata (1952)

6 Allegro con brio

III: Bernhard Krol – Sonata op. 17 (1954)

7 Presto

III: Bernhard Krol – Sonata op. 17 (1954)

8 Maestoso

III: Bernhard Krol – Sonata op. 17 (1954)

9 Allegro assai

V: Hermann Reutter – Pièce concertante (1968)

V: Hermann Reutter – Pièce concertante (1968)

11 Exposition

V: Hermann Reutter – Pièce concertante (1968)

12 Berceuse

V: Hermann Reutter – Pièce concertante (1968)

13 Combination

VI: Kurt Fiebig – Variations on a Theme of M. Clementi (1952)

14 Thema. Un poco adagio

VI: Kurt Fiebig – Variations on a Theme of M. Clementi (1952)

15 Variation 1. Andante

VI: Kurt Fiebig – Variations on a Theme of M. Clementi (1952)

16 Variation 2. Allegro moderato

VI: Kurt Fiebig – Variations on a Theme of M. Clementi (1952)

17 Variation 3. Allegro molto

VI: Kurt Fiebig – Variations on a Theme of M. Clementi (1952)

18 Variation 4. Adagio

VI: Kurt Fiebig – Variations on a Theme of M. Clementi (1952)

19 Variation 5. Con brio

VI: Kurt Fiebig – Variations on a Theme of M. Clementi (1952)

20 Variation 6. Allegretto grazioso

VII: Günter Raphael – Sonata op. 74a (1957)

21 Con moto

VII: Günter Raphael – Sonata op. 74a (1957)

22 Vivace

VII: Günter Raphael – Sonata op. 74a (1957)

23 Allegro molto energico

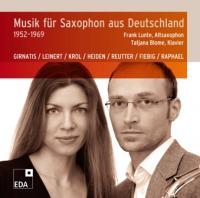

Music for Saxophone from Germany 1952–1969

The present compilation Music for Saxophone from Germany 1952–1969 showcases outstanding compositions from the first two postwar decades and complements the three-part CD series Music for Saxophone from Berlin (EDA 21: 1930–1932; EDA 22: 1934–1938; EDA 29: 1982–2004).

The exploration of the saxophone as a classical instrument began in the German capital in the 1930s. Abruptly interrupted by repression and war, it found its continuation only in the 1980s. The euphoric mood of the postwar years saw the continued stigmatization of the saxophone, which had been classified as “degenerate” by the National Socialists. After the Second World War, the National Socialists’ ambivalent relationship to the saxophone impeded a unprejudiced view of this versatile instrument by the younger composers living in Germany. The cultural guardians of the Third Reich did not consider the saxophone suitable for art music, and presented it as a “nigger instrument” and with erotic-sexual innuendos. This campaign ultimately led to a general ban that was later lifted again – albeit only for “good,” that is to say, “German” music. In the journal of the “Kampfbund für Deutsche Kultur” (“Battle League for German Culture”) one even solicited sympathy for the saxophone, which however “would have to liberate itself from its bad company and turn to beautiful melodies.” The periodical Deutsche Zukunft (“German Future”), on the other hand, demanded the continued banishment of the saxophone from German orchestras, since it was “a foreign and Jewish import.” Nevertheless, the powers that be also employed the instrument selectively, even prescribing it for certain purposes and appropriating it in their own way. However, the actual attitude of the culturally and politically relevant NS institutions is obvious from the poster for the 1938 “Degenerate Music” exhibition in Düsseldorf: an elegantly dressed, saxophone-playing black dance musician with a Star of David on his lapel (an allusion to Ernst Krenek’s opera “Jonny spielt auf”) reveals beyond a doubt the National Socialists’ perfidious view of the saxophone.

The saxophone must have seemed abstruse to the composers; the many breaks and contradictions in its recent history did not make it a trustworthy instrument. Celebrated, banned, vaunted, discredited, honored, vilified, misappropriated, praised, maligned, applauded, stigmatized – for serious concert use, it was better to keep one’s distance from this “strumento non grata”. Due to its prominent use in jazz, as well as in revue, band, and popular music, it posed problems for the composers who, following the radical musical break of those years, saw in Adorno’s anti-tonality dogma their calling in serial, aleatoric, and later increasingly experimental music, and additionally turned to electronic means, and therefore to the controllable manipulation of the sound up to and including a defined tonal presentation that was not left exclusively to the performer. Since the saxophone, as a glitzy symbolic instrument, was still linked to jazz, and in the 1920s–30s borrowings from this popular style, along with the use of the saxophone, appeared in serious compositions, it did not fit into the instrumentarium of the avant-gardists; they largely excluded “the suspicious saxophone.”

The serialists in the musical centers of the postwar avant-garde in Cologne, Darmstadt, and Donaueschingen saw the foundation of their creative process in Adorno’s Philosophie über neue Musik (“Philosophy of Modern Music”), published in 1949, in which the renunciation of beauty was postulated and the deconstruction of the musical material advocated. The major triad was considered reactionary and fascistic. Whoever considered himself to be a composer committed to democracy accepted Adorno’s dogma of a strict separation of popular and serious music and refrained from anything that could have aroused a suspicion of allegedly restorative thinking. Further comments by Adorno, also concerning the saxophone, did their part: “Not just the saxophone is borrowed from the military bands, but indeed the whole disposition of the jazz orchestra, with its melody, bass, “obbligato” accompaniment, and purely filler instruments, is identical to that of the military bands. For this reason, jazz will be quite suitable for use by the fascists.” (“Über Jazz,” Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, Paris, 1936, under the pseudonym of Hektor Rottweiler)

As a result of the increasing presence of serialism and the compositional trends following it (and also their sponsorship by public authorities, including the broadcasting syndicates), tonal and free-tonal oriented compositional techniques became marginalized. To be sure, there were a large number of composers who resisted the hostility toward tonality and wrote in a conventional-traditional style, but their works received little or no attention and often fell into oblivion. The works recorded here are also largely unknown and to the present day have not found their way into the core repertoire of classical saxophonists. The quality of these works, on the other hand, is undeniable. They bear witness to a serious consideration of traditional composition techniques for a modern wind instrument. Half of the works on this CD are recorded here for the first time.

Frank Lunte