V: Alberto Ginastera – Puneña No 2 "Hommage à Paul Sacher" op. 45 (1976)

Please select a title to play

I: Sándor Veress – Sonata per violoncello solo (1967)

I: Sándor Veress – Sonata per violoncello solo (1967)II: Ursula Mamlok – Fantasy Variations for cello solo (1982)

II: Ursula Mamlok – Fantasy Variations for cello solo (1982)

6 With increasing excitement

III: Marcel Mihalovici – Sonate pour violoncelle seul op. 60 (1949)

8 Grave

III: Marcel Mihalovici – Sonate pour violoncelle seul op. 60 (1949)

9 Allegro moderato

III: Marcel Mihalovici – Sonate pour violoncelle seul op. 60 (1949)

10 Mosso

III: Marcel Mihalovici – Sonate pour violoncelle seul op. 60 (1949)

11 Molto adagio

III: Marcel Mihalovici – Sonate pour violoncelle seul op. 60 (1949)

12 Allegro non troppo

IV: Ahmet Adnan Saygun – Partita "To the Memory of Friedrich Schiller" op. 31 (1955)

13 Lento

IV: Ahmet Adnan Saygun – Partita "To the Memory of Friedrich Schiller" op. 31 (1955)

14 Vivo

IV: Ahmet Adnan Saygun – Partita "To the Memory of Friedrich Schiller" op. 31 (1955)

15 Adagio

IV: Ahmet Adnan Saygun – Partita "To the Memory of Friedrich Schiller" op. 31 (1955)

16 Allegretto

IV: Ahmet Adnan Saygun – Partita "To the Memory of Friedrich Schiller" op. 31 (1955)

17 Allegro moderato

V: Alberto Ginastera – Puneña No 2 "Hommage à Paul Sacher" op. 45 (1976)

18 Harawi

V: Alberto Ginastera – Puneña No 2 "Hommage à Paul Sacher" op. 45 (1976)

19 Wayno Karnavalito

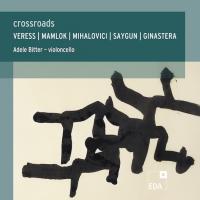

"In the arts there are no foreigners" (Brâncuși)

Five voices get a chance to speak here: five individuals who have entrusted works to the cello in which the freedom of self-determination, in the aesthetic as well as in the ethical sense, is expressed in an impressive manner. Five points of view that show how complex identity is, and how dangerous and precarious the growing desire for identitary simplification in all social and political areas.

Homeland and inclusion, exile and foreignness, sedentariness and migration are constants in human history. Yet, what does birth, nationality, mother tongue, and father tongue, the cultural environment of childhood mean? What does upbringing, character, and assignation to a group mean for the life of an artist? What does a composer, a musician make out of the experiences of emigration, and what effects do these experiences have on the works?

As a native of Berlin with a relatively modest migration radius – I completed a part of my training in Frankfurt am Main, my first engagement took me to the Badische Staatstheater Karlsruhe – I discovered "the foreign" only later, sometimes coincidentally, but for all that consciously. I owe my first glimpses over the boundaries of classical European music to the teacher of my adolescent years, Gerhard Mantel. For he introduced me to numerous contemporary works, also including compositions by Isang Yun, a South Korean living in Germany, which have continuously accompanied me to the present day, and that I have meanwhile released in a complete recording of all the works for violoncello and piano, duo and solo, together with pianist Holger Groschopp.

Advanced studies at the "Hanns Eisler" College of Music with Prof. Joseph Schwab, for his part a Hungarian-born German, provided the necessary tools to be able to address the music of all stylistic epochs and traditions that are available in the huge violoncello repertoire. Actually – for initially the predetermined goal was to be accepted into a renowned orchestra. I had the good fortune to become a member of the Deutsches Symphony Orchestra Berlin: the homesickness for my native city was healed. The desire to provide a contribution to the rediscovery of forgotten compositions, to stoke the audience's curiosity for artistic, sometimes intellectual challenges – this desire is satisfied on a regular basis and continually finds new fertile soil.

Within the framework of supplementary studies in historical performance practice at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, I experienced once again how infinitely broad the field of one's own instrumental work is, and what comprehensive education is required to even be able to make judgements. The work in the DSO constantly calls for this degree of knowledge and ability. I am indebted to this ensemble and its guests for motivation, inspiration, journeys, and friendships – but above all, the daily encounter with people from over twenty countries sensitizes one for questions of identity and danger.

Music is vulnerable and not immune to misuse. Again together with Holger Groschopp, a recording has now come into being with works for violoncello and piano by Simon Laks, who due to his Jewish descent was deported to Auschwitz and appointed there director of one of the camp orchestras. Laks, who had settled in Paris in 1926 and returned there after the end of the war, could not save the music from the worst abuses, but literally owed his survival to it.

With its incomparable capacity to emerge time and again from the transitions and spaces, and to blend together the seemingly unfamiliar, music can point the way for people crossing the borders. The program on this CD unites five works by five composers – close together in the period of the second half of the twentieth century, close together through the common fate of a life informed by migration, emigration, and flight; close together also in the obvious non-inclusion in the predominant musical avante-garde of the time. And they are united by the precious individuality with which they illustrate the "inexhaustible diversity between the worlds" (Christoph Schlüren).

I owe a debt of gratitude to Ursula Mamlok, who in the few short encounters substantially influenced my self-perception as a musician – and to Bettina Brand, who made possible the personal meeting, and thus also to the Dwight and Ursula Mamlok Foundation for the financial support for the realization of this recording project. Frank Harders-Wuthenow accompanied this recording from the idea to the completion with never-ending inspiration, Lukas Kowalski with empathy, great artistic insight, and humorous motivation, Daniel Kogge and Yves Gateau with patient understanding for the difficulties of my stressed instrument (Gustave Bernardel, Paris 1899); Yigit Aydin from the Bilkent Saygun Center and Felix Meyer from the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel provided valuable iconographic material and sources. I would like to express my thanks to all of them.

Adele Bitter, November 2021

All of the composers brought together on this album left their homelands for longer periods during the course of their lives. This happened for very different reasons. For their studies, the Romanian Marcel Mihalovici and the Turk Ahmet Adnan Saygun went to Paris, where they received formative impressions. Saygun returned to Turkey, Mihalovici remained for the rest of his life in France, where due to his Jewish descent he had to go underground during World War II, and survived in hiding. Although held in high regard in his own country, the Hungarian Sándor Veress chose the path of Swiss exile in view of increasing political repression. Switzerland also became a second homeland to Argentine Albert Ginastera toward the end of his life. For Ursula Mamlok, finally, the emigration to America, which she took upon herself at the age of sixteen, was the escape from the certain death that awaited her as a Jewess in National Socialist Germany.

However, they are all linked not only by the crossing of geographic borders. The personal change of location was always also connected with an artistic change of perspective, which let the artists see their previous work in another light. In the foreign countries that for most of them transformed into new homelands, they received new inspirations, learned new expressive possibilities that led to modifications of their personal styles, partially to veritable changes of style. The works recorded here bear witness equally to the tensions that can arise between the origins and that which has been acquired, as well as to the possibilities of synthesis. The works of Veress, Ginastera, and Mamlok are informed in different ways by the occupation with twelve-tone technique, which in the case of Veress and Ginastera encounters a musical language rooted in folklore. Saygun and Mihalovici cross borders of another kind. For both, Johann Sebastian Bach stands in the background as a great inspiration. The art of the German baroque master is reflected both in modern urbanity as well as in the ancient traditions of Balkan and Anatolian folk music.

The erection of the Iron Curtain after World War II did not just divide Europe into two geographical and ideological blocs, but also caused a decisive break in the biographies of numerous artists. For the Hungarian Sándor Veress, the political division of Europe not only became the reason to go into exile in Switzerland, but also the starting point of a stylistic reorientation. Born in 1907, Veress grew into a musical life that was already substantially informed by the ideas of Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály. With their scientific research into Hungarian peasant music, and also into the folk music of Rumania, Slovakia, and Asia Minor, Bartók and Kodály had established a folklore-based stylistic ideal that clearly differed from the style, oriented on German models, of their teacher Hans Koessler, and that served as a guideline for the composers of the following generations. Veress, who in the second half of the 1920s studied in Budapest with Bartók and Kodály, was also greatly influenced by it. In 1930, he followed his teachers' example and undertook a journey to Romanian Moldavia in order to research the music of the Csángós, a Hungarian-speaking minority, The occupation with folk music was to accompany him from then on for the rest of his life, be it as an active artist, researcher, or pedagogue. Thus, starting in 1935, he initially collaborated as assistant under Kodály's direction, later as Bartók's successor on the preparation of the Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungariae. His reputation in this field spread also outside of Hungary, so that in 1948 he was invited to be a member of the jury at the International Eisteddfod in Llangollen, Wales (a function he held until 1984), and also appeared as an official delegate at the Congress of the International Folk Music Council in Basel.

In 1945 Veress joined the Communist Party, since it – shortly after the end of World War II – seemed to him to open the best perspectives for the reconstruction of Hungary. Yet, already as the communists insidiously seized power during the following three years, Veress developed an increasing skepticism toward them. He started planning his emigration to the West in 1947. In 1949, after a journey to performances of his ballet Térszill Katicza in Stockholm und Rome, he did not return to his native country, but went to Switzerland. His initially conceived plan to settle permanently in the USA failed because there – at the high point of McCarthyism – one begrudged him his membership in a communist party. Veress therefore remained in Switzerland until the end of his life. Owing to bureaucratic obstacles, he received Swiss citizenship only in December 1991, less than three months before his death. However, already shortly after moving to Switzerland, he found access to musical life there. From 1950 to 1981 he taught as Professor of General Music Education and Composition at the Bern Conservatory, between 1968 and 1977 he held a professorship in music ethnology at the University of Bern.

Veress remained devoted to folk music throughout his life. However, during his last years in Hungary, the folkloristic ideology of the communist authorities strengthened him in his plan to leave the country. The greatest inspiration that the West offered the emigrant was the twelve-tone technique, which he integrated into his works starting in the 1950s. Yet, informed by thinking in folkloristic, modal tonal systems, Veress preceded undogmatically and used all the possibilities to mitigate the latent rigidity of dodecaphony.

An example of his free handling of twelve-tone rows is offered by the Sonata for Violoncello Solo, which he composed in 1967 for cellist Mihály Virizlay, a Hungarian emigrant who had lived since 1957 in the USA and who was a strong advocate for contemporary music. All three movements begin with a twelve-tone theme (in the finale, the row is hidden in the opening chords and the two tones of the following trill), yet they all also contain numerous passages in which the twelve tones are not all to be found. The frequent interaction of intervals of the fourth, fifth, and second additionally make for constant tonal centering. In the first movement, designated "Dialogo," dialogues take place on a number of levels: between more animated and moderate tempos, between high and low registers, between twelve-tone and free passages. The "Monologo" of the second movement begins softly and intensifies in the middle to tremolo eruptions that resonate tremblingly in the concluding section. In the rapid "Epilogo," the player can freely fashion the tempo. Bar lines are found only around the pizzicato passages at the beginning, in the middle, and at the end.

Ursula Mamlok's life was impacted early on by migration. Born in 1923 in Berlin as the daughter of Jewish parents, she experienced as a child how the National Socialists deprived the Jews of the right to view Germany as their homeland and gradually banished them from societal life. That Ursula Levi was able to attend school on a regular basis until she was sixteen was due only to the fact that her stepfather, as a former soldier who served in World War I, was at first spared the deprivation of his rights and persecution. However, in 1938, the year of the Reichspogromnacht, even that no longer provided protection. In February 1939 the family boarded a ship that took them to Ecuador. The aspiring composer spent a year and a half in the culturally pallid port city of Guayaquil. From the very beginning, she viewed the United States as the actual goal of her emigration. Several compositions that she sent from Guayaquil to Clara Mannes, the head of the Mannes School of Music in New York, were decisive in obtaining a scholarship in the USA. Since she could only get an entry permit for herself, but not for her parents, the seventeen-year-old had to undertake the journey to New York alone. The family was reunited again in North America only in 1941. In 1947 Ursula Levi married the merchant and author Dwight Mamlok, who later wrote the texts to some of her vocal works – he, too, was a Jewish emigrant who had just barely escaped the grasp of the National Socialists in 1939. The couple initially lived in San Francisco, but moved in 1949 to New York, where Ursula Mamlok taught music theory and composition at New York University, Temple University (Philadelphia), and, from 1975 until her retirement in 2003, as professor at the Manhatten School of Music. After the death of her husband in 2006, Ursula Mamlok decided to move to Germany. She returned, as a highly honored personality in international musical life, almost seven decades after her compelled emigration, to Berlin, the city of her childhood, where she died in 2016 at the age of ninety-three.

As an adolescent, Ursula Mamlok enjoyed a solid training with Gustav Ernest, a pupil of Philipp Scharwenka's, in the traditional compositional techniques of the nineteenth century, and could already boast numerous works of her own when she began advanced studies at the Mannes School with George Szell. However, the more she occupied herself with the tendencies of modern music of that time – Ernst Krenek and Eduard Steuermann had introduced her to the music of Arnold Schoenberg – the more she felt the classical traditions to be constraining. She explored numerous styles, continued her studies with such varied teachers as Roger Sessions, Jerzy Fitelberg, Erich Itor Kahn, Vittorio Giannini, Stefan Wolpe, Gunther Schuller, and Ralph Shapey, but only in 1961 was she convinced to have found her own personal expression – at a time when her craftsmanship had already earned her three composition awards (1945, 1952, 1959). Almost all of Mamlok's mature compositions make use of twelve-tone technique. She did not adopt this from any one of her teachers, but rather discovered it independently for herself, and found in it the expressive means of her own style. In the organization of her music, Mamlok did not limited herself strictly to the four outward forms of a basic twelve-tone row, but obtained series of tones through diagonal or spiral-form progressions within a twelve-tone square, which are new, but nevertheless prescribed by the row.

The Fantasy Variations for Violoncello Solo were written in 1982 during a very prolific creative phase. The four-movement work, which is characterized by a terseness of expression typical of Mamlok, draws on a number of pieces that the composer created in the 1960s for solo instruments, but sets new accents through a playfully relaxed attitude. In this composition, Mamlok was obviously particularly fascinated by the use of the violoncello's tonal possibilities for the fashioning of imaginary dialogues. Thus, the first movement develops out of a dialogue between bowed and plucked notes. In the slow final movement, the high registers enter into a dialogue with the low registers. Between the high-contrast first movement and the reserved finale, which concludes in ppp, are two short movements. The second has the effect of a concentrated variant of the first movement. The third movement works itself up into increasingly rapid figurations.

Marcel Mihalovici moved within three cultural regions. Born in 1898 in Rumania, he spent sixty-six of his eighty-seven years of life in France. After World War II he attained great esteem in German-speaking regions. The foundations of this border-transcending life were laid in his childhood: Mihalovici stemmed from a well-to-do home and grew up in Bucharest in culturally inspiring circumstances. He spoke fluent French and German at an early age, especially liked playing German classics on the violin, but raved above all about the music of Debussy. He shared the love of French culture with his great compatriot George Enescu, who in 1919 advised him to study composition in Paris. Thus, the barely twenty-one-year-old Mihalovici enrolled as a student at the Schola Cantorum, where he was taught until 1925 by Vincent d'Indy and Paul Le Flem, among others. In Paris, Mihalovici, who sometimes dabbled as a painter, quickly found access, also apart from music, to circles of modern artists. Among his closest friends were the sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi, the dancer Lizica Codreanu, and her sister, the sculptor Iréne Codreanu, all three likewise stemming from Rumania. In the sphere of publisher Michel Dillard, who had specialized in the dissemination of the works of foreign artists resident in Paris, Mihalovici made the acquaintance of the Czech Bohuslav Martinů, the Hungarian Tibor Harsányi, and the Swiss Conrad Beck, who together with him made up what was designated by the press as "L'Ecole de Paris" or "Groupe des Quatre" – the universally admired Albert Roussel called them "les constructeurs." In 1932 Mihalovici was a founding member of Triton, a society for contemporary chamber music. In the pianist Monique Haas, who frequently participated in the society's concerts, Mihalovici found his wife and muse, who inspired him to compose numerous piano and chamber music works.

Owing to their Jewish descent, Mihalovici and Haas no longer felt safe in Paris after the entry of the German army in 1940. They fled to Cannes in the unoccupied part of France, where they lived in seclusion together with the Codreanu sisters. As members of the Front national de la musique, they participated in clandestine acts of resistance against the occupiers starting in 1942.

After the war, Mihalovici attained the zenith of his fame. On the one hand, his works were frequently broadcast on French radio, on the other, starting in 1950, he found access to the musical life of West Germany and Switzerland through his acquaintance with conductors such as Hans Rosbaud, Ferdinand Leitner, Heinz Zeebe, Paul Sacher, and Erich Schmid, as well as with Heinrich Strobel, the director of the Southwest German Radio (SWF), who was very influential in the circles of Germany's postwar avant-garde. In France as well as in the German-speaking countries, his compositions were now regularly found on the programs of contemporary music festivals. However, this was in no way linked to tendencies toward avant-garde attempts at atonal styles.

Mihalovici's Sonata for Violoncello op. 60 was written in 1949 for cellist André Huvelin, a close friend from the circle of the so-called Ecole de Paris. Huvelin had not only championed the composer's works – for example, in 1946 he participated in the premiere of the Sonata for Violin and Violoncello, op. 50 – but in 1944 was also a helper in an hour of need when he offered Mihalovici and Haas refuge in his castle in Mont-Saint-Léger (Franche-Comté) after the Gestapo had found out about their hiding place in Cannes. In the years after the war, Mihalovici and his composer friends held annual gatherings at Huvelin's estate.

In the five short movements of the Sonata, Mihalovici's outstanding sense for tonal relationships is evident. Each movement emanates from a different tonal center. Self-contained is only the opening Grave, which begins and ends in C Minor. However, all the other movements, regardless of the key with which they start, also turn toward C Minor at the end, which thus has to be considered the principal key of the whole work. Within this framework, a modulatory occurrence of a great density of events takes place. Tonal changes of direction already within individual phrases are the rule. A traditional cadencing by means of clear dominant harmonies are also avoided, whereby the music is permanently held in a tense state of harmonic suspense. This is resolved each time in the concluding C-Minor chords of the individual movements.

Ahmet Adnan Saygun, who was born in 1907, numbers among the first Turkish composers to have enjoyed a professional training in Western Europe, and yet remained all his life spiritually rooted in the musical traditions of his native country. Having grown up during the last years of Ottoman rule and the first of the republic founded by Kemal Atatürk, he experienced profound social changes at an early age. Thus, during his youth fell, on the one hand, the 1925 law enacted during the course of the Kemalist secularization concerning the closure of the dervish convents, which directly affected the composer's father, who was a member of the Mevlevi order. On the other hand, the state founder's cultural policy opened unexpected possibilities of advanced artistic training to the young Ahmet Adnan, who at the age of seventeen already worked as a music teacher, and had mastered both the piano as well as the ‘ūd, an oriental short-neck lute. Although Western European music had already long been accepted in Turkey (in 1828, at the behest of Sultan Mahmut II, Giuseppe Donizetti reorganized the palace wind band in accordance with the western model and introduced occidental musical notation, and from 1839 the Francophile Sultan Abdülmecid I made the piano and Parisian salon music popular in Istanbul's high society), it was only under Atatürk that this was an issue of greatest importance, and that large-scale Turkish art music was created on the basis of the most modern occidental achievements. In 1928 Saygun won a state composition competition and received a scholarship for further training at the Schola Cantorum in Paris, where he studied composition with Vincent d'Indy. The courses with Amédée Gastoué and Eugène Borrel sharpened his senses for the similarities between Gregorian chant and Sufi music. After his return in 1931, Saygun himself trained music teachers. In 1934 Atatürk appointed him conductor of the President's Symphony Orchestra. A research trip through Southwestern Anatolia, undertaken in 1936 together with Béla Bartók, laid the foundation for his reputation as the leading Turkish music ethnologist of his time. In 1946 Saygun was appointed Professor of Composition at Ankara Conservatory. His oratorio Yunus Emre on verses by the Turkish popular poet of the same name, which was premiered that same year, finally brought him the international breakthrough as a composer.

Saygun's music-aesthetic statements clearly reveal the influence of Sufi concepts. The undogmatic attitude with which he confronted musical phenomenon, his quest for knowledge, and the scepticism toward the fashions of the day are ultimately a legacy of the Mevlevi into whose traditions he was born. He very critically viewed the modern "extremes of the ego" and the resulting "endeavor to tear everything down," "to shake everything to its foundations." He countered the absolutization of the "self" with an aesthetic of integration. He in no way considered it a sin to speak of influences: "To be a holy man, one has to go through severe ordeals, and those who endure the ordeals of the arts will be on the lookout for their sheikhs. Let us keep the influences holy."

The Partita for Violoncello Solo, op. 31, is such an integrative work. Saygun composed it in 1955 "to the memory of Friedrich Schiller" as a commission from the director Max Meinecke, who was active at the Istanbul Municipal Theater at the time. It was premiered on 15 April of the same year by Martin Bochmann, violoncello professor in Ankara, within the framework of a memorial celebration on the 150th anniversary of the poet's death in the German Consulate General in Istanbul, after which the composer and the performer were awarded a Schiller medal. In spite of the title, it is not a composition in baroque style. Johann Sebastian Bach's Cello Suites did not serve Saygun as a stylistic, but rather as an ideational point of contact. Just as Bach ennobled the Baroque dance music through the power of his personality, Saygun proceeded here with melodic and rhythmic topos of Turkish folk music. He profusely ornamented the modal-based melodies with chromatic steps, and only one movement (no. 4, with its siciliano reminiscences, the "most Western" of the work) does not contain a change of time. The work begins in C with characteristic major-minor alternations. In the rhythmically intricate second movement, the tonal center wanders to D-flat. The Phrygian mode dominates in no. 3 (E) and no. 4 (G). The lively finale returns to C and concludes with a reprise to the opening of the first movement.

When asked which quality was the most important to him in a work of art, Alberto Ginastera answered: "transcendence." It is therefore not surprising that his own artistic output is characterized by a continual crossing and interpenetration of spaces, times and styles – and it may seem symbolic that he died in Switzerland while working on Popol Vuh, a symphonic reflection on the story of the creation of the Maya. Born in Buenos Aires in 1916, Ginastera developed early on a sense for the multifaceted nature of life and art. He grew up in the capital of an emerging immigrant country, the largest metropolitan area in South America at the time, which completely dominated Argentina economically and culturally and, through its international relations, drew attention to Europe and North America. A stark contrast to the life of the "porteños" (literally: port city dwellers) was offered by the pampa, the vast, flat, sparsely populated hinterland that fascinated Ginastera even in his childhood, not least because of the by no means idyllic legends that grew around the lives of the gauchos and Indios. The pampa transitions in the distance into the puna, the highlands of the Andes, which extend all the way to Peru and with that allude to the high culture of the Incas that was wiped out by the Spanish conquerors. These three geographical areas, their culture as diverse as it is contradictory, and their history riddled with fault lines, form the spiritual background for Ginastera's compositions. His life was naturally not untouched by the events of Argentine history: during Perón's rule, which he opposed, he was suspended from his teaching positions; after the military coup in 1966 he undertook a number of long trips abroad, and ultimately emigrated to Switzerland in 1977.

Ginastera was the first Argentine composer whose music found international dissemination. Having completed his entire training in Buenos Aires, he entered the North-American and European stages only in 1945 and 1951, respectively, as a finished and respected artist who already held a professorship in his hometown. Nevertheless, from the very beginning he was cognizant of the developments in Europe, revered Debussy and Stravinsky, and found a role model in Béla Bartók with regard to the artistic fashioning of folkloristic music. In the 1950s he discovered Alban Berg, whose method of twelve-tone composition oriented on tonal centers attained great importance for his own works. Ginastera never committed himself entirely to a specific idiom or style. Even in later years, when he constructed most of his compositions out of twelve-tone rows, he by no means disavowed the roots of his works in Argentine folklore. It is thus hardly expedient to divide his life's work into phases. Ginastera responded during the course of his life to a wide variety of influences which interfuse one another in his compositions, and chose his stylistic means in accordance with the expression aspired to in each case.

Puerto, pampa, and puna each inspired Ginastera to a series of works. Thus, in 1950, he wrote three compositions for different instrumentations, which he named Pampeanas. These were to be followed in the 1970s by three Puneñas, of which he however only completed no. 2, op. 45, intended for solo violoncello. Officially, the two-movement work was written in 1976 at the suggestion of Mstislav Rostropovich in order to honor Paul Sacher, the notable Swiss conductor and patron of the arts, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday. Yet at least a just as big influence on the genesis can be attributed to cellist Aurora Nátola, the composer's second wife, with whom he lived in Geneva from 1971. Ginastera understood this "mountain piece" as a "recreation of the sound world of the mysterious heart of South America, which was formerly the Inca Empire." He was always conscious of the irretrievable loss of the pre-Columbian cultures, including the greater part of their music. He therefore felt their influence on his works, in contrast to Hispanic-American influences, "not as folkloristic, but rather as a kind of metaphysical inspiration." In Puneña no. 2, the recreation stems from different sources. Thus, the "metamorphosis of a pre-Columbian theme from Cuzco" is found as the second theme of the introductory Harawi (Love Song). It is formed however out of six notes that supplement Sacher's name, on which the first theme is based (eS-A-C-H-E-Re [eS = E-flat; Re = D]), to make up a twelve-tone row. The composer characterized the second movement, a lively Wayno, as a "wild, tumultuous carnival dance […] full of the rhythms of the charango and Indian drums, colorful costumes, ponchos, and masks, as well as corn schnapps." The Sacher theme is found here, too. Numerous measures of the movement are to be played "pizzicato alla chitarra" – a tribute to the Hispanic folklore instrument par excellence.

Norbert Florian Schuck

(Übersetzung: Howard Weiner)