III: Johann Anton André – String Quartet No. 1 in C major op. 14

Please select a title to play

I: Johann Anton André – Sonata for Piano, Violin and Cello op. 17

I: Johann Anton André – Sonata for Piano, Violin and Cello op. 17I: Johann Anton André – Sonata for Piano, Violin and Cello op. 17

1 Allegro con moto

I: Johann Anton André – Sonata for Piano, Violin and Cello op. 17

2 Andantino quasi Adagio

I: Johann Anton André – Sonata for Piano, Violin and Cello op. 17

3 Rondo Allegretto

II: Johann Anton André – Duo No. 2 in G major op. 27

4 Allegro commodo

II: Johann Anton André – Duo No. 2 in G major op. 27

5 Rondo Allegretto

III: Johann Anton André – String Quartet No. 1 in C major op. 14

6 Allegro brioso

III: Johann Anton André – String Quartet No. 1 in C major op. 14

7 Andante moderato

III: Johann Anton André – String Quartet No. 1 in C major op. 14

8 Menuetto – Allegro scherzoso ma brioso

III: Johann Anton André – String Quartet No. 1 in C major op. 14

9 Allegretto Vivace

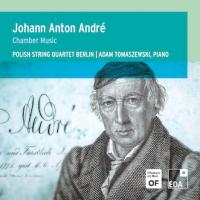

The question of why Johann Anton André (1775–1842) is one of the most thoroughly forgotten composers is one that defies simple answers. One could make it easy for oneself and invoke the lack of quality of his music as a reason, but then one would have to explain which standards are to be applied in order to be allowed to make such a judgment. And this is where it gets difficult: Someone who composes like Beethoven or Mozart or Haydn and is not named Beethoven or Mozart or Haydn is quickly labeled (by posterity) as an "epigone" – indeed skilled in his craft and beyond reproach, but intellectually inflexible and only capable of imitation. Seventy-five years ago, in the encyclopaedia Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, music researcher Helmut Wirth summed up the matter in the form of a statement representative of the general view of history: As a composer, Johann Anton André was "close to the art of Haydn and Mozart, but lacked style-setting influence." Basta, one would like to say; and add that one is not actually doing oneself or the world at large any favors by dealing with such things. This is however the view of posterity, whose cultural memory in any case has capacity limits and therefore only offers space for outstanding achievements, which are often enough defined retrospectively. The contemporaries thought differently; they (naturally!) did not care whether someone would later be classified as "style-setting," and those who overstated the case were viewed with suspicion. In a manner of speaking, all who participated in musical life creatively, reproductively, or as an audience sitting in a comfortable armchair were fishing in one and the same pond. They shared a consensus regarding the forms and material, social communication and, above all, listening expectations.

If one has the courage to join these contemporaries and someday venture out of the protected space of high culture, which is only perceived in connection with certain names, the reward for the effort is a very special experience. The question is no longer how good or how bad or how independent or even how "style-setting" Johann Anton André’s music ultimately was, but what was the character of the musical world into which he was born in 1775. One encounters a family with a migrant background that integrated splendidly and achieved affluence: the Offenbach silk factory produced luxury goods; its customers had leisure time at their disposal, which they liked to fill with theater and music, and since father Johann André also had great musical talent, he combined business experience with artistic inclination and, a year before his son was born, founded a music publishing company that soon became his primary activity. Johann Anton André numbered among the privileged young people who were able to freely develop their intellectual gifts. One really does not need to rack one’s brain concerning the teachers with whom he studied, who were quite well-known at the time (and today forgotten) – the important thing is to imagine that he had and used the opportunity to absorb everything that was happening in the sphere of music. His father’s publishing house was frequented by those who had or aspired to distinction; that which was being played in Paris, London, and Vienna as well as at the courts and in the commercial centers was available, and by means of its own editions the publishing house itself contributed to the development of the tastes of its clientele, who in turn lived not only in the region but in half of Europe. No one can doubt that Johann Anton André knew all the many names, musical conventions, and rapidly changing fashions, innovations, and trends. Likewise, one should not be surprised that he not only took every opportunity to make music alone or with others, but also at some point, perhaps driven by adolescent exuberance, to take up the quill himself, assuming that his insightful father would include the first composition – penned in 1789 – in his publishing program. The foundations had long been laid when, ten years later, Johann Anton André succeeded his father, who had died in 1799. In addition to the many demands of his work as a publisher, André continued to pursue – certainly not only out of personal inclination – his compositional ambitions. This was also a signal to the customers: The businessman knows something about that with which he is trading; and it indeed turned out that this composing businessman established himself over time as one of the leading authorities in questions of music theory, as documented by his Lehrbuch der Tonsetzkunst ("Textbook on the Art of Composition") – published in 1832–43.

Johann Anton André had already composed and also published a whole series of his own works – including symphonies, concertos, sonatas, and lieder – when he turned to the string quartet genre. Whoever did this in the period around 1800 was confronted even then with very strict standards, which were oriented above all on Joseph Haydn; André had only recently issued Mozart’s now famous last ten string quartets (as reprints of the Viennese originals) in his publishing house, following them immediately with six early works (as first editions). He himself thus made a not inconsiderable contribution to the canonization of the master, but never dreamed of entering into competition with Mozart or Haydn (or even Beethoven, whose first quartet cycle op. 18 had been published in Vienna only a few weeks earlier). He would otherwise not have expressly designated his six quartets of op. 14 and op. 15 as quatuors concertans, with reference to the specific tradition that had developed above all in Paris: what is meant is not the complex and often contrapuntal movement form, not the (often later defined) ideal of a pensive grappling with compositional problems in the form of intellectual flights of fancy, but rather a continuous gliding of melodic lines through the voices as the defining characteristic. The first quartet of the Trois Quatuors concertans op. 14 is a good example of this manner of composing and playing music in this scoring, which by this time had already been cultivated for several decades. The fact that the composer was not only interested in tastefully crafted, well-balanced entertainment is demonstrated in particular by the expansive first movement; in keeping with custom, it conforms to the sonata form, but offers unexpected effects, as if the composer wanted to play with the established listening habits: the recitative-like cadenza in the extended development is a surprising moment that hardly anyone at the time would have expected. The Andante and Menuetto that follow – both certainly most closely obliged to convention – also do not spare with fresh turns. And the at first seemingly harmless finale, with its recitative-like solo passages that in their dramatic gesture are certainly not meant to be entirely serious, proves to be a decidedly humorous contribution to the quartet literature – and indeed with great potential for catchy tunes and the composer’s obeisance to Haydn and Mozart, who had already made the most of the amusing effect of general pauses at the very end. By the way, the composer dedicated the Quartets op. 14 to the Offenbach tobacco manufacturer and amateur violinist Peter Bernard, who was certainly quite pleased to receive this gift from his friend André.

The Piano Trio, published in 1802 as op. 17, does not however bear a dedication; André probably did not want to link it to a single and, on top of that, prominent person, but rather to offer a contribution to a very widespread and still extremely popular musical tradition that was not oriented on public performance, but on private domestic conviviality. Accordingly, the composer followed the traditional principle of the accompanied piano sonata, known for example from Haydn and Mozart as well as many others, in which the string instruments must subordinate themselves; the violoncello is even expressly marked as dispensable ("ad libitum") and doubles the bass of the piano or, at the octave, the violin part, respectively. Nevertheless, one cannot imagine the piece without "accompaniment," since in spite of the convention being observed, the composer shows himself able to create a balanced and varied, sometimes virtually soothing sonority – for example, by means of long sustained notes in the strings. And this may have been the actual challenge, for the equality of the instrumental parts had only shortly before occurred to Beethoven as a self-given compositional task with a view to high musical demands: Johann Anton André was concerned rather about creating music in which, under the guidance of a more experienced player, the other participants would have an active part in the technical success and euphony of playing together without being exposed to the danger of having to capitulate to excessive demands – in an ideal situation it was perfect family music and an incentive to continue practicing diligently. The three-movement work with a sonata movement followed by an Andante variation concludes, entirely in accordance with the tradition, with a rondo that however really has something special: surprising passages in minor and other dramatic, downright cleverly fashioned interjections show that André had more in mind than a predictable, lively, but at some point also boring finale, of which there were already countless examples.

With his two Violin Duos op. 27, which were likewise issued by his publishing house, namely in 1805, André served a field that was associated even more with the pedagogical domain than the accompanied piano sonata and that at the time was also perceived as such: unlike the string quartet and piano trio, to a lesser extent one has and had an established genre with corresponding norms and compositional conventions, but rather a form of instrumentation that was to be explained very pragmatically, which was also available for other instruments and that could address the cooperation between teachers and students as well as the equitable playing of two pupils. In the meantime – typically, however, without the participation of the classical composers still renowned even today – a huge repertoire, also including arrangements, had developed due to the continuing demand. And it may well have been owing to business calculations that André again proffered a dedication: Madame (Agathe-Victoire) Ladurner, whose name appears on the title page, lived in Paris as an acknowledged violin pedagogue, and since the French capital was an important trading center for André’s musical goods, she was able – to put it in modern terms – to act as an influencer for Offenbach’s publishing products and especially for the duos. She presumably commended them with the observation that they were something quite different from the mass-produced works for advanced students that were then so widespread in France: one was confronted with solid musical literature with compositional demands, and the challenge consisted (and consists) not only of overcoming any technical difficulties, but in particular in the forming of a nearly equitable interaction, whereby the otherwise familiar chamber music sound with omnipresent bass voice is lacking this time. Perhaps it is precisely for this reason that the two-movement Duo is the one composition among those from the quill of Johann Anton André brought together on this CD that makes the greatest demands on the performers as well as undoubtedly on the audience endowed with considerable listening experience.

Axel Beer (April 2024)

(english translation: Howard Weiner)