V: Hans Winterberg – String Quartet No. 1 (1936)

Please select a title to play

I: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Cello and Piano (1951)

I: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Cello and Piano (1951)I: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Cello and Piano (1951)

01 Allegro moderato

I: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Cello and Piano (1951)

02 Mit ausdrucksstarker Bewegung

I: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Cello and Piano (1951)

03 Vivace

II: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Viola and Piano (1948/49)

04 I (ohne Tempoangabe)

II: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Viola and Piano (1948/49)

05 II (ohne Tempoangabe)

II: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Viola and Piano (1948/49)

06 III (ohne Tempoangabe)

III: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Trumpet and Piano No. 1 (1945)

07 Allegro moderato

III: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Trumpet and Piano No. 1 (1945)

08 Intermezzo

III: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Trumpet and Piano No. 1 (1945)

09 Vivace

IV: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Violin and Piano (1936)

10 Agitato grazioso

IV: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Violin and Piano (1936)

11 Andante con moto

IV: Hans Winterberg – Sonata for Violin and Piano (1936)

12 Molto vivace

V: Hans Winterberg – String Quartet No. 1 (1936)

13 Allegretto

V: Hans Winterberg – String Quartet No. 1 (1936)

14 Molto tranquillo

V: Hans Winterberg – String Quartet No. 1 (1936)

15 Allegro vivace

....................................................................................................

Nominated for the German Record Critics' Award in the "Chamber Music" category (Quarterly Critic's Choice – Long List 1/2025)

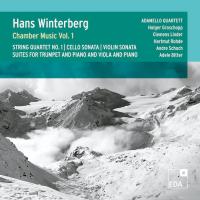

"The Only Human Place"

There are probably few comparably disrupted biographies in musical history, and yet Hans Winterberg’s life is paradigmatic of the convulsions and horrors of the European twentieth century, which he lived and suffered through practically from beginning to end. He was born in Prague in 1901 and died in 1991, shortly before his ninetieth birthday, in Steppberg, a small Upper Bavarian town located between Nuremberg and Munich. Hans, or Hanuš Winterberg, as he also called himself in the 1920s and 1930s, deserves places in the Austrian and Czech, as well as in the German, but above all in European musical historiography. He has been denied the former, and the latter has yet to be written. To help provide the sounding evidence is one of the aims of our label. With this Vol. 1 of a series dedicated to Hans Winterberg, we want to honor another important composer whose work is difficult to pin down from the perspective of national music historiography, but whose importance cannot be overestimated from a transnational perspective.

Hans Winterberg was a child of the Habsburg monarchy, a multi-ethnic state in which a multitude of ethnicities, languages, cultures, and religions coexisted and got along with each other. Until its demise at the end of the First World War, Austria-Hungary was the opposite of a nation in the "modern" sense – a state structure characterized by ethnic, linguistic, and religious homogeneity, as demanded then and now by identitarian movements – contrary to all the dynamics of history. Hans was the scion of an assimilated Jewish family. His father ran a cloth factory with his brother-in-law in northern Bohemia. Like most of the Jews who had settled in Bohemia since the reign of Maria Theresa, the family was German-speaking. Until the proclamation of Czechoslovakia at the end of the First World War, German was the school and administrative language. Literary figures in Prague, such as Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, Franz Werfel, Egon Erwin Kisch, and Gustav Meyrink, wrote in German. In the 1930s, Werfel was one of the favorite poets of the song composer Winterberg. As a piano prodigy, Hans had lessons with the renowned pianist Therese Wallerstein. Starting in 1920, he studied at the newly founded German Academy of Music and Performing Arts: composition with Fidelio F. Finke, conducting with Alexander von Zemlinsky, who, in addition to his position as music director of the New German Theater, also directed the Academy. After graduation, Winterberg initially worked as a répétiteur and conductor at the theaters in Brno and Gablonz.

In 1930, the first census was carried out in Czechoslovakia in order to gather data about the makeup of the country's ethnic groups and languages. Winterberg's family declared themselves to be Czech, although they had belonged to Prague's German-speaking Jewish community for centuries. It is no longer possible to determine whether this was due to loyalty to the pro-Semitic government of Tomáš Masaryk or to pure pragmatism: Winterberg's father was probably also dependent on government contracts. Perhaps they did not want to belong to yet another minority, since the German-speaking population was no longer the dominant force in politics and culture after 1918. In 1930, Hans married the pianist and composer Maria Maschat, the interpreter of his works until after the war. In 1935, their daughter Ruth was born. The marriage to a German "Aryan" initially protected Hans Winterberg after the annexation in 1939 of the Czech rump state by Nazi Germany. However, so-called privileged "mixed marriages" at best provided a delay of the measures that had as their goal the extermination of the Jewish population. Surprisingly, Winterberg's marriage was not forcibly dissolved until 1944. Someone possibly held a protective hand over him, since as a forced laborer he was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto only in January 1945. This saved his life. With the exception of Walter Süsskind and Walter Kaufmann, who managed to escape to England and India, respectively, in 1938, and Karel Ančerl, who survived Auschwitz, the entire Czech-Jewish musical elite was sent from Theresienstadt to their deaths in Auschwitz in the fall of 1944. Erwin Schulhoff, who should also be mentioned in this context, died in an internment camp in Bavaria already in 1942.

1945, zero hour. Hans Winterberg was left with nothing. His mother, like his piano teacher Therese Wallerstein, had been murdered in the Belarusian extermination camp Maly Trostinec in 1942. His father Rudolf had died in 1932, his company forcibly expropriated in 1939. The life of Rudolf Winterberg's brother-in-law Hugo Fröhlich ended in Dachau. The Jewish friends and colleagues were dead or in exile; the others fell in the war or fled to Germany during the course of the expulsion of the German-speaking population from Czechoslovakia. Assaults and massacres against the "Sudeten Germans," as they were summarily designated, and who were indiscriminately blamed for Hitler's extermination policy, culminated in March 1946 in the ratification of the so-called Beneš Decrees – measures to expel all citizens who had registered as German or Hungarian in the 1930 census. Among them also Maria Maschat and her daughter Ruth, who fled to Bavaria. Hans Winterberg, however, stateless as a Jewish forced laborer and concentration camp inmate, regained Czech citizenship in the summer of 1945, because his family had declared themselves to be Czech in 1930. To the present day, the circumstances of his life during the period leading up to his emigration remain unclear as to what he did and from what he lived. And why he followed his wife and daughter to Bavaria only in 1947. To be sure: for a survivor of the Shoah, Germany in 1945 was not exactly the destination of all dreams. The paths of Jewish emigration tended to lead to Israel, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, or the USA. Winterberg applied several times for permission to leave the country on the grounds that he wanted to retrieve his scores, which he had moved to safe places in other European countries before his deportation. After the second or third trip to war-ravaged Munich, he was never to return to Prague.

Hans Winterberg's decision to emigrate to West Germany in 1947 was probably prompted by family and professional considerations. Maria Maschat had lived in Munich with her daughter Ruth since their expulsion from Czechoslovakia. Although the marriage, even without a forced divorce, appears to have fallen apart already during the war, Maria Maschat and Ruth were still Winterberg's closest surviving relatives. And important professional contacts from the pre-war period meanwhile held positions in German musical life. Presumably, the looming Communist takeover also ultimately shattered the prospect of continuing to live in Czechoslovakia. Upon his arrival, Hans Winterberg, the Shoah survivor with a Czech passport, registered as a refugee, which he actually was not. His identity card initially identified him as stateless, then one deemed him an "ethnic German." This was followed by years of grappling with the German authorities until in 1950 he was granted German citizenship by dint of his marriage to a voice student. As a concentration camp survivor, he received a onetime compensation of a few thousand marks, a reparation for his mother was rejected by the authorities: he was older than sixteen at the time of her murder. Maria Maschat, who had regained a foothold as a pianist, used her contacts to help him get jobs as a freelance collaborator at the Bavarian Radio and the Richard Strauss Conservatory in Munich. Winterberg established contacts with former friends from Prague, such as Fritz Rieger, who after his position as chief conductor in Mannheim, assumed the direction of the Munich Philharmonic in 1949. With the Mannheim Orchestra, Rieger premiered Winterberg's First Symphony in 1949, and a year later, with the Munich Philharmonic, the First and then also the Second Piano Concerto as well as the Symphonic Epilogue, with which Winterberg commemorated the victims of the Shoah.

In the 1950s, Heinrich Simbriger, a fellow student of Winterberg's in Finke's class and founder of the music archive of the Esslingen Artists' Guild, from which the Sudeten German Music Institute later emerged, became something of a savior for Winterberg, who now entered the circle of the Sudeten German Homeland Association. A double-edged sword, for Simbriger tried to bring him into the Sudeten-German fold. Winterberg played along with the game, plagued by constant existential fears, and later certainly also compelled by his fourth wife Luise-Maria Pfeifer – a Sudeten German. From her first marriage to an SS man, Marie Luise brought a son, Christoph, into the relationship. In the 1960s, Winterberg had a falling out with his daughter Ruth, who suffered from severe psychological disorders, and never met her son Peter, his grandson. Christoph, whom Winterberg had adopted and made his sole heir, ran an antiquarian bookshop in Munich, and was apparently extremely paranoid and driven by anti-Semitic resentment. Upon selling Winterberg's estate to the Sudeten German Music Institute in 2002, he had Winterberg's musical legacy provided with a restriction clause: until the end of 2030, no one should know of its existence, and the composer's Jewish ancestry must be categorically suppressed.

It is thanks to his grandson Peter Kreitmeir that Hans Winterberg's music is no longer hidden from the eyes of the public in the high-security zone of a German music archive. Just a few months after Peter's birth, his father separated from his wife, Winterberg's daughter Ruth. Peter, who grew up with his father, had no further contact with his mother. He knew about his grandfather only from hearsay and was entirely unaware of the existence of a step-uncle. In 2004, he set out in search of his roots, his mother's family, and his Prague ancestors. It was to be an odyssey. It was years before he stood for the first time before his grandfather's inaccessible legacy at the Sudeten German Music Institute in Regensburg. Some one hundred compositions from six decades: a dozen symphonic works, four piano concertos, ballets, chamber music, songs, and piano works. An incredible treasure. At Kreitmeir's insistence, Christoph Winterberg rescinded the restriction clause. Research on a lost protagonist of twentieth-century classical modernism could begin.

During his lifetime, Hans Winterberg did not have a publisher. This means that there was not a single printed edition of any of his compositions, i.e., a final version. New editions of all the works presented on this CD – four of them first recordings – were made within the framework of the cooperation between the Exilarte Center of the Vienna University of Music and the music publishers Boosey & Hawkes. The source situation varies from work to work, and in many cases is not entirely unproblematic due to divergences between the sources and ambiguities regarding dynamics and phrasing. For works that were never performed during the composer's lifetime, such as the First String Quartet (Symphony for String Quartet) from 1936, we can only speculate about a definitive version that might have been created during the rehearsal process. However, the performance material of works which Winterberg himself rehearsed with performers does not provide any indication that he later undertook fundamental changes in his fair copies.

Winterberg's documented, i.e., preserved, oeuvre spans almost sixty years from the Suite for Piano of 1928 to the last piano pieces from 1984/85. His musical cosmos is a symbiosis of preconscious impressions, i.e., those experienced in childhood, and conscious appropriations that reflect his cultural awareness, an awareness that transcended the borders of national restrictions. In a letter to Wolfgang Fortner – in his function as director of the Bavarian Radio's Musica Viva concerts – dated 6 December 1967, Winterberg sketched his artistic career:

"As a composer, I became acquainted with and also worked in all the musical trends that emerged in our century, starting with Impressionism through the Expressionism of the 1920s, during which time the atonal line of serial composition by Arnold Schönberg and his successors also came into being. Since my emigration from Prague to Germany (after the second war), I have also attentively followed all the new developments. Nevertheless, after many detours, I have only now found my way to a direction that represents something like a new path, a new, perhaps very free variant of serial composition."

If Schoenberg's influence was still clearly evident in the Piano Intermezzi of 1929, for example, then Winterberg had found his very own style by the mid-1930s at the latest, the potential of which he systematically explored in the following decades, as shown by the selection of works on this CD. In addition to his ability to integrate heterogeneous material (which does not preclude its confrontation), it is above all Winterberg's pronounced interest in rhythmic processes that stands out, where he followed a path predetermined by Janáček but atypical for the Western European avant-garde (and that only came forward again in a dominant way in late Ligeti). Although Winterberg's stylistic points of reference – Debussy, Bartók, Schoenberg, and Hindemith – emerge in his compositions in very different forms, they all have in common the playing with polymetric and polyrhythmic processes. In a letter to Simbriger in 1955, he attributed this to the influence of the musical traditions of his homeland, speaking of "traces of Eastern folklore, above all in rhythmic moments." However, he continued, "these elements are informed by a harmony (especially in my later works) that is definitely of Western origin, I mean this of course in the broadest sense." Even if the commitment to German culture expected by Simbriger led him to state that his harmonies were based on Western, above all German-Austrian models, in his music he made no secret of the sources from which he drew – most obviously in the final movements, which are carried by dance-like impulses. The proximity to the music of Hans Krása or Pavel Haas is evident. And here, above all, it becomes clear how Winterberg, after the Second World War, continued and further developed a tradition that seemed to have been demolished with the annihilation of nearly an entire generation of Czech composers.

Preserved in the archive of the Exilarte Center in Vienna are folders with press clippings from the composer's legacy, which provide information on the performance history of his compositions. The material on the chamber music works is meager. In a handwritten list of works, which Winterberg compiled toward the end of the 1960s and then amended accordingly, the works that were performed and for which sound recordings existed are indicated. However, this list of works is incomplete, since manuscripts had gone astray already during Winterberg's lifetime, manuscripts which were found by his grandson in the estate of Winterberg's second wife. For some compositions, the source situation suggests that they were never performed – when, for example, there is only a score, but no individual parts.

Winterberg's Cello Sonata from 1951, which opens the selection of works on this CD (which we have arranged contrary to the timeline for reasons of musical dramaturgy), was possibly accompanied by the composer himself at a performance, as suggested by an annotated copy of the score. Nothing is known about the cellist, about the venue and time of the concert, or about later performances during Winterberg's life. The Cello Sonata – Winterberg's only contribution to this genre – is a perfectly crafted, virtuoso, extremely effective, but also deeply moving piece in which the characteristics of his personal style are clearly evident and that is therefore an outstanding introduction to his style. With its three-movement structure and short duration of less than thirteen minutes, the work displays neoclassical restraint – verbosity, contemplation, and romantic fervor are alien to Winterberg. But in his works, succinctness and brevity always go hand in hand with intensity and an exuberant abundance of action within a small space. It is music whose sinews are stretched to the breaking point. The first movement introduces us to the almost inexhaustible cosmos of Winterberg's rhythmic games of deception. The metrical decidedness of the defiant, indeed angry march with which the movement begins is immediately sabotaged. That which Winterberg develops out of the ternary cell of the iambic rhythm so characteristic of the Czech language as well as of Czech music is admirable; it dominates the audacious second part of the exposition and gradually also overruns the march theme. The constant disruption of the measure accents by asynchronous syncopations is taken to extremes in the third movement, where a small manipulation in the piano's left-hand accompaniment is enough to make us believe for a moment that ragtime had its origins in Czech folklore. The hyperactivity of the outer movements is sharply contrasted by a meditative, highly emotional slow movement, a large vocal scene for the cello, as if it were a "Souvenir de Prague" from the pen of late Fauré, but with "deeper shadows … than we know from French music."1

Fritz Rieger's activities as a mediator can be traced back to the creation of chamber music works. The Viola Suite, for example, is dedicated to Dr. Carl Weymar, the founder of the Bachwochen, where Rieger had been a regular guest since moving to Ansbach in 1948. Winterberg evidently wrote the piece especially for the dedicatee, who was a violist. However, the source situation suggests that it was never performed. Winterberg originally conceived it for harp and viola, but probably "came to the realization while working on the piece that the pedal changes required in many passages could hardly or not at all be implemented on the harp at the necessary speed and that the part could probably be played more easily on the piano".2 The Suite is – perhaps also owing to the original accompanying instrument – the most "impressionistic" of the works compiled on this CD, a little jewel that allows the magical and mysterious character of the viola to sound in the most beautiful way.

The First Suite for Trumpet was composed in Prague in 1945 after Winterberg's return from Theresienstadt. Nothing is known about a performance in his home town. Winterberg must have had it in his luggage when he decided to relocate to Bavaria in 1947. It is uncertain whether the performance organized by the Munich Studio for New Music in Amerika-Haus on 2 March 1950 was the world premiere, since the program does not identify the performance as such. Interestingly, performed in the same concert, alongside Winterberg's trumpet suite, was also a song cycle by Maria Maschat and excerpts from a piano suite by the fourteen-year-old Hans Zender, whose tender age is specially noted. The performers of the suite were Willy Brem (trumpet) and Agi Brand-Setterl, who also premiered Winterberg's First Piano Concerto with the Munich Philharmonic under Fritz Rieger in the same year. As with the cello sonata and the trumpet suite, striking is the depth of Winterberg's understanding of the character and style of playing of the solo instrument, how skillfully and confidently he handled the "idiom" of the trumpet.

In Winterberg's handwritten catalogue of works, the date of composition of his (only) Violin Sonata is given as 1935; on the manuscript itself he noted "Prague, 18. XI 1936", whereby for inexplicable reasons he used the French and English spelling instead of the German "Prag" or Czech "Praha." To be found in Winterberg's press portfolio is an undated review of a performance before the war, in which neither the venue nor the performers are named. However, the paper and typeface suggest that it originated from the German-language Prager Abendblatt. The critic noted that the composer exploited "all the technical possibilities of the violin apparatus” and “does not eschew reliable sound effects in the motivic mosaic." For all that, the sonata is anything but a superficial bravura piece. As in the concurrently written First Symphony, in which Winterberg later saw a premonition expressed of the coming catastrophe, and also in the First String Quartet, Winterberg's unconventional treatment of traditional forms is impressive. The weighty first movement, in terms of duration as long as the second and third movements together, begins with a prelude-like introduction followed by an extended process of thematic development. Two melodic turns of phrase, which dominate the further course of the movement, gradually crystallize from simple intervallic constellations: a rotating five-note motif that successively fills the tonal space of a major third chromatically, then a descending diatonic formula that is strongly reminiscent of the folk song "Schlaf, Kindlein schlaf," which we also encounter again in later works by Winterberg. The original elan increasingly dies out and gives way to a melancholy pensiveness, until ultimately the movement nearly freezes in an indecisive state of uncertainty. The second movement also does not want to commit itself to a basic character, adamantly beginning like a passacaglia and austere "like a funeral procession," but the violin plays freely and can even persuade the piano to enter into a lyrical dialogue before both return again to the gravitas of the beginning. The brash, at times gruffly eruptive last movement is unashamedly folkloristic, a rondo with strongly contrasting sections and a wealth of intricate polyrhythmic layers which reveal completely new aspects of listening pleasure to the listener who is now familiar with the very specific challenges of Winterberg's music.

Winterberg's First String Quartet from 1936 – titled "Symphony for String Quartet" by the composer – has a curious but, in the context of Winterberg's Kafkaesque biography, also somewhat typical story. Winterberg managed to preserve the manuscript during the war, and also succeeded in taking it with him when he emigrated to Munich in 1947. However, he forgot it, leaving it with his second wife, the singer Heidi Ehrengut – who had helped him attain German citizenship through marriage in 1950 – after their separation. He apparently did not remember it when in the late 1960s he compiled his catalogue of works, in which the piece – like others he had left with her – is absent. So it came to pass that the manuscript was not part of the estate that found its inglorious way into the Sudeten German Music Archive in 2002. Peter Kreitmeir came across it during his own research. However, the last page was missing from the bundle of music, having been wrongly allocated to a different manuscript. This part of the great Winterberg puzzle could only be resolved recently during research after the Amernet Quartet had already completed its Winterberg production (Toccata Classics).

Winterberg's First String Quartet is perhaps his most complex and demanding work from the pre-war period. It fills us with gratitude and awe to have been able to recover and bring to light this jewel – "a masterpiece not only of Czech music, but of the entire string quartet repertoire of the twentieth century"3 – almost ninety years after its creation. In terms of the interpretative challenges and the particularities of its stylistic approach, it occupies a place between the quartets of Janáček and his pupil Pavel Haas and the quartet compositions of the protagonists of the Second Viennese School. On the other hand, hardly to be found are connections with the aesthetics of the Prague quarter- and sixth-tone composer Alois Hába, with whom Winterberg undertook additional studies at the end of the 1930s. Whoever wants to understand the fascination of Winterberg's music or, even better, immerse and let themselves be carried away by it, must give their ear time to get used to a different, new prioritization of the parameters. From the Renaissance to the avant-garde of the 1920s, we were taught to concentrate above all on melodic and harmonic processes that are carried by a rhythm. In Winterberg, the rhythm takes on a primordial significance that it has not had in European art music since the music of the late Middle Ages. Harmonic and melodic developments serve over long stretches almost as a "contrast medium" in order to make rhythmic processes, rhythmic complexity tangible.

The quartet "symphony" is linked to Winterberg's first symphony by its disguised three-movement structure – disguised, because there are no self-contained movements, but a latent tripartite structure that shows itself by means of drastic changes of tempo and character (Molto tranquillo – Allegro Vivace). While the slow middle section clearly sets itself apart from the two outer movements, the third section takes up the material and processes of the first, concluding cyclically with a reminiscence of the beginning of the work, which results in a large, superordinate tripartite song form: A– B–A'.

In a conversation with his fourth wife, the painter and poet Luise-Maria Pfeifer, recorded on tape on 23 March 1977, his seventy-sixth birthday, Winterberg reflected on the questions of music and identity, and on the problems of his own artistic existence, which had been expelled from the pluralistic cosmos of the K. & K. (i.e., the Habsburg monarchy's imperial and royal) culture. "If someone does not represent and feel a nation within themselves, then they are a zero, so to speak, then they are nothing," he summed it up bitterly, only to really explode about the implications of this statement: "What does nationality mean? What kind of backward, twisted concept is that!" At the end of his life, the Austrian composer Ernst Krenek, who was born just a few months before Winterberg and died just a few months after him, ironically and aptly summed up the crux of the fate of exile, and his conclusion also applies unequivocally to Winterberg, even if the biographical demarcation line was an ocean for one and an Iron Curtain for the other: "During the course of the last twenty years, I have often toyed with the idea that it must be possible to exist as a citizen of the world, as an Austrian and an American, but that is certainly a chimera that cannot withstand the pressure of reality. The result is that one floats between two continents or sits between two chairs, which may ultimately prove to be the only humane place to be."4

For more information about the life, afterlife, and work of Hans Winterberg, please visit the website of his grandson Peter Kreitmeir: https://kreitmeir.de/petersuchtmama, Michael Haas's blog https://forbiddenmusic.org/2021/05/27/the-winterberg-puzzles-darker-and-lighter-shades and the website of his publisher Boosey & Hawkes www.boosey.com/Winterberg.

Frank Harders-Wuthenow

(english translation: Howard Weiner)

______________________

1 Michael Haas, Preface of the Edition, Boosey & Hawkes, Berlin 2024.

2 Holger Groschopp, Editorial Report in the first edition, Boosey & Hawkes, Berlin 2024.

3 Michael Haas, Preface to the first edition, Boosey & Hawkes, Berlin 2024.

4 Ernst Krenek, "Von Kakanien zur Wahlheimat," in: Das Jüdische Echo, Vienna 1990.